Revenue Administration: A Toolkit For

Implementing A Revenue Authority

William Crandall and Maureen Kidd

Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre

and

Fiscal Affairs Department

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Technical noTes and Manuals

TNM/10/08

International Monetary Fund

Fiscal Affairs Department

700 19th Street NW

Washington, DC 20431

USA

Tel: 1-202-623-8554

Fax: 1-202-623-6073

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Fiscal Affairs Department

Revenue Administration:

A Toolkit For Implementing A Revenue Authority

Prepared by Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre

(William Crandall and Maureen Kidd) in collaboration with the

Revenue Administration Division of the Fiscal Affairs Department

Authorized for distribution by Carlo Cottarelli

April 2010

JEL Classification Numbers: H20, H24, H25

Keywords: Revenue Authority, revenue administration, governance, tax compliance,

autonomy in tax administration, accountability, tax, customs

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this technical manual are those of the authors and

should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 1

Revenue Administration: A Toolkit For Implementing

A Revenue Authority

Prepared by Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre

(William Crandall and Maureen Kidd) in collaboration with

the Revenue Administration Division

TECHNICAL NoTEs ANd MANUALs

Contents

overview ................................................5

i. introduCtion and BaCkground to revenue authorities............8

A. Some Terminology......................................................8

B. What Is a Revenue Authority? .............................................8

C. Making the Decision to Proceed ..........................................10

D. Conclusions Reached about RAs .........................................14

E. Revenue Authority Websites .............................................14

ii. PoliCy ChoiCes ...................................................15

A. A Framework for Policy Choices ..........................................15

B. Degree of Autonomy ...................................................15

C. Governance Framework ................................................15

D. Accountability ........................................................16

E. Scope ..............................................................16

F. Analytical Matrix for Policy Choices—a Module ...............................16

iii. legislative issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Introduction ............................................................23

A. The Need for Enabling Legislation .........................................23

B. Reflecting the Policy Choices ............................................23

C. Working with the Ministry of Justice .......................................24

D. The Relationship with Other Laws .........................................24

E. Structuring the RA Law .................................................25

F. Managing the Parliamentary Timetable......................................26

G. Checklist for Developing RA Draft Legislation—a Module .......................26

iv. transitional Provisions..........................................28

Introduction ............................................................28

2 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

A. Transitional Provisions—Excluding Initial Staffing ..............................29

B. Transitional Provisions—Initial Staffing ......................................31

v. organizational issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Introduction and Background ..............................................37

A. Modern Customs and Tax Administration Organizations ........................37

B. The Relationship between Tax and Customs Administration in the RA..............38

C. Organizational Considerations in Tax Administration ...........................39

D. Prototype Organization for a Revenue Authority ..............................41

E. Specific Organizational Considerations .....................................42

vi. oPerational readiness...........................................46

Introduction ............................................................46

A. Phases of RA Implementation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .46

B. Hiring and Start-up of the Chair, Board, Secretary and CEO .....................47

C. Development of Management Policies......................................50

vii. ProjeCt ManageMent............................................53

Introduction ............................................................53

A. The Importance of Project Management ....................................53

B. Project governance ....................................................53

C. Project Methodology and Approach .......................................55

D. Constraints ..........................................................56

E. Typical Project Management Plan .........................................56

viii. CoMMuniCations ................................................57

Introduction ............................................................57

A. The Need to identify Core Communications Themes ...........................57

B. Internal Stakeholders—Messages and Challenges ............................58

C. External Stakeholders—Messages and Challenges ............................59

D. Evaluating and Monitoring Communication Results ............................60

E. An Organization Structure for Communications ...............................60

F. Consultation Strategy...................................................60

G. Developing Key Communications Messages—a Module........................61

iX. reforM and Modernization ......................................63

Introduction ............................................................63

A. Creating a Revenue Authority—the Importance of Reform and Modernization ........63

B. Building on Existing Reform Plans .........................................63

C. Specific Reform Initiatives for the New Revenue Authority .......................64

D. Overseeing Reform—Organizational Solutions................................68

E. Developing a Reform Plan for the RA.......................................69

F. What is Needed to Make a Reform and Modernization Program a Success? .........70

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 3

X. inforMation teChnology .........................................71

Introduction and Background ..............................................71

A. Domestic Tax and Customs IT Issues ......................................71

B. IT Support for the New RA ..............................................72

C. Longer Term IT Strategy and Funding ......................................73

Xi. Change ManageMent .............................................74

Introduction ............................................................74

A. Change Management—the Organization....................................74

B. Change Management—People ...........................................75

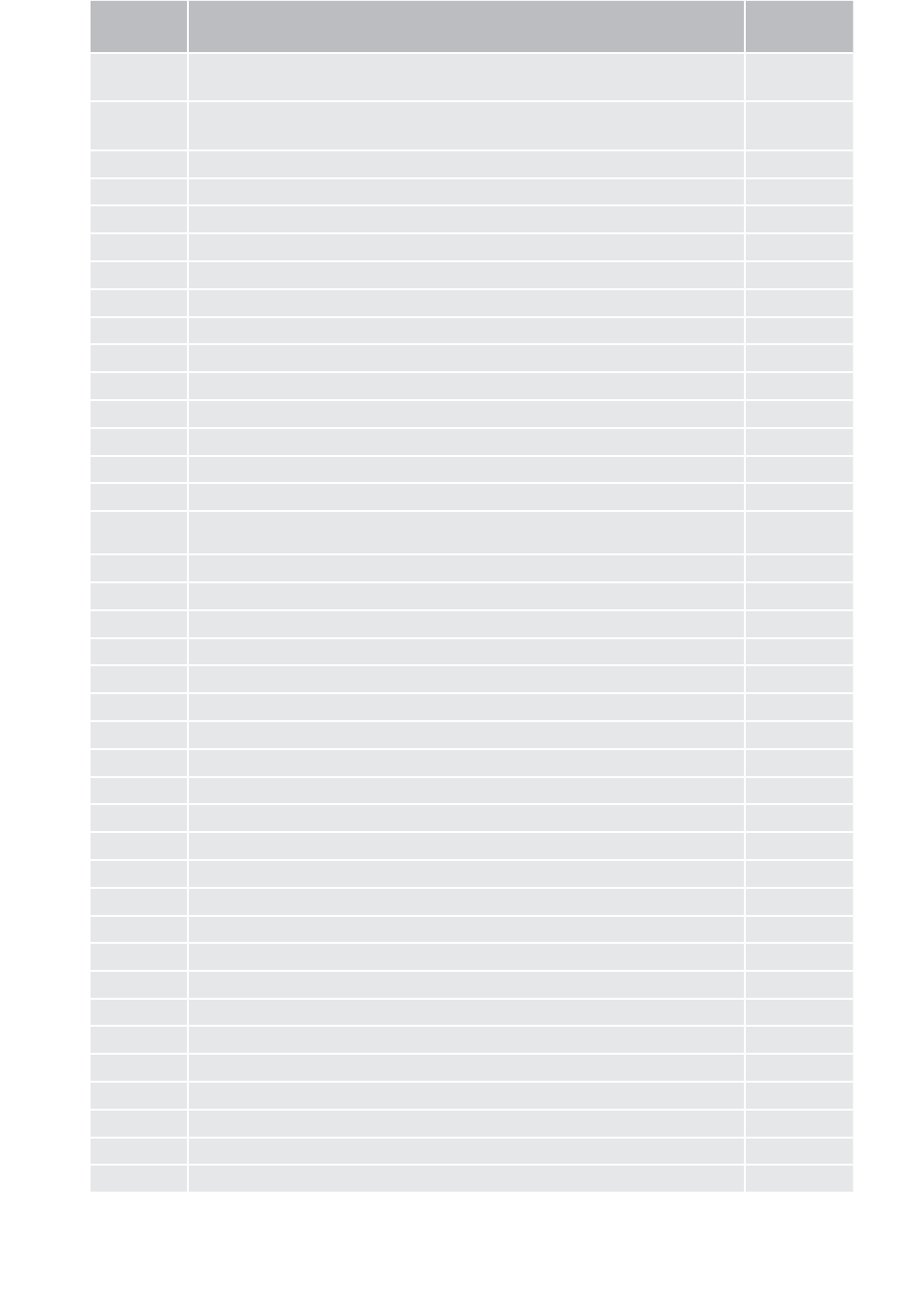

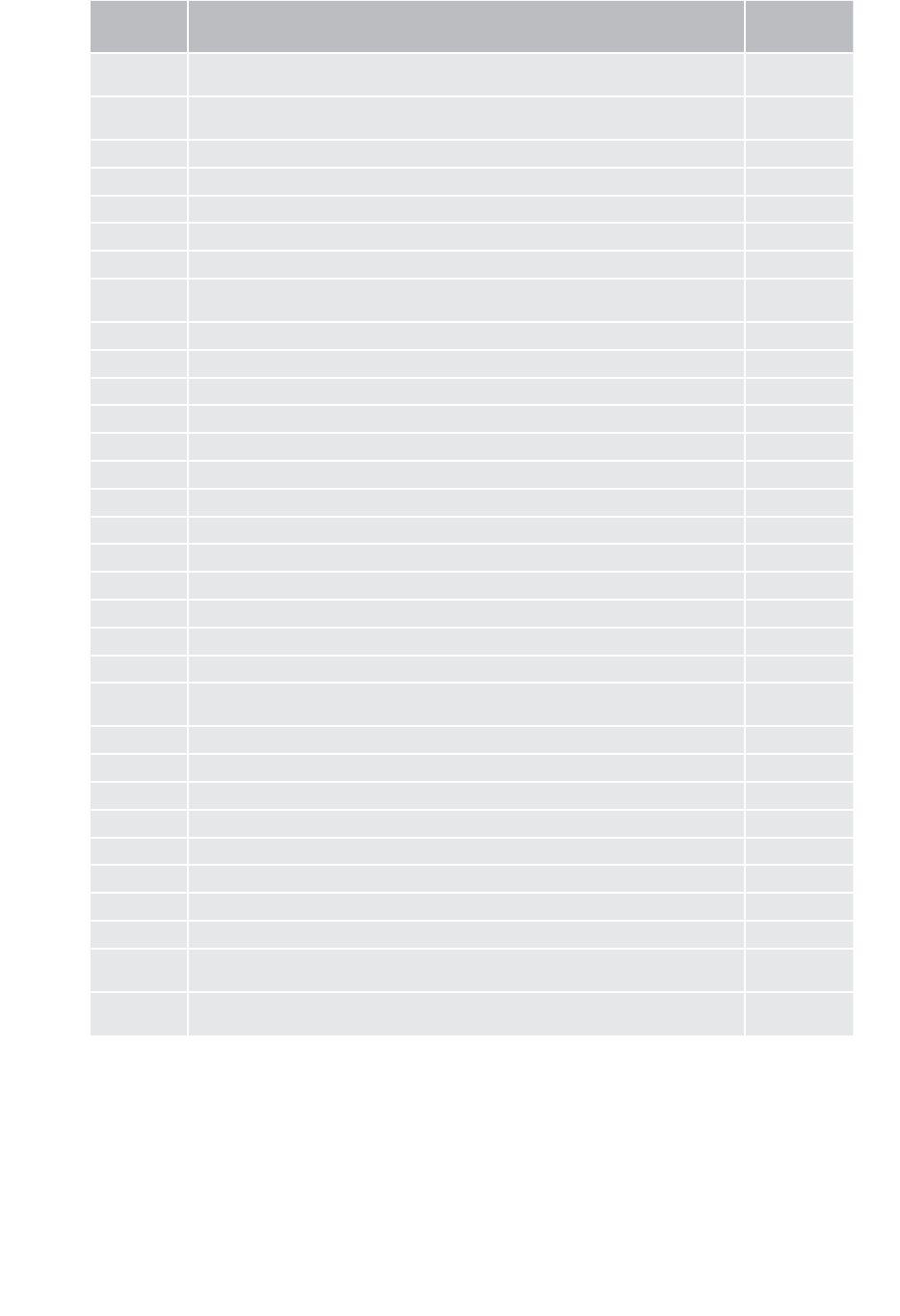

taBles

1. Reasons (ranked) for Implementing a Revenue Authority ........................10

2. Analytical Matrix for Policy Choices ........................................17

3. Checklist for RA legislation...............................................27

4. Preparation for Transition to the RA ........................................30

5. Worksheet for Initial Staffing..............................................36

6. Worksheet for Determining Organizational Options ............................45

7. Worksheet for Developing Key Communications Themes .......................62

figures

1. Autonomy and Revenue Administration Governance ............................9

2. Typical Organization Chart for a Revenue Authority ............................43

3. Three Phases of RA Implementation .......................................47

BoXes

1. Sample Board Member Profile ............................................49

2. Common Features of Revenue Administration Modernization ....................64

aPPendiXes

I. A Commentary on Specific RA Legislation ...................................77

II. Salient Steps Within a Revenue Authority Implementation Plan ..................108

referenCes ........................................................112

4 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 5

overview

In the context of discussions concerning the possible establishment of revenue authorities (RAs) in

Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) countries, CARTAC undertook to provide the ECCB with

a “toolkit” to assist member countries in making important implementation decisions.

This toolkit is a guide with a series of operational modules designed to assist countries when they

implement a “revenue authority’ (a more autonomous organizational structure) to administer their

tax and customs operations.

This toolkit is developed to respond to an identified need. It is different from much of the previous

theoretical or anecdotal writing on revenue authorities in that it is designed as a series of tools for

countries to use in mapping out the implementation of a revenue authority—once a decision to

proceed in this direction has been made.

Each of the following chapters first sets the stage, explaining why the subject is important to the

design and implementation of the RA. If appropriate to the subject, working modules are then

presented in a manner to make review and analysis of the country’s own circumstances as clear

and straightforward as possible

The toolkit is grouped into 11 chapters as follows:

Introduction and background for Revenue Authorities—This chapter provides a definition

of Revenue Authority, a brief history of the concept, terminology, identification of key research

documents, a discussion on increasing autonomy in public institutions, and a review of why

countries choose the RA model for their revenue administration (Chapter I).

Policy choices—No two RAs are alike although all have common features. Governments must

make policy choices in terms of degree of autonomy, the governance framework, accountability

and scope, and such policy choices need to be based on the specific objectives for establishing

the RA and be informed by what other countries have done. This chapter provides an operational

guideline for determining the features of a revenue authority. It includes an operational module

countries can use to support logical and comprehensive decision-making (Chapter II).

Legislation—Establishing a RA will necessitate enabling legislation and such legislation needs to

follow the policy decisions, not lead them. Most RA implementation is approached in two stages—

policy and legislation first, then operational implementation. Legislation is the critical front

piece. This chapter outlines the need for separate enabling legislation, discusses typical legislative

components, identifies known “trouble spots” and emphasizes the importance of a legislative

package that reflects the approved policy choices (Chapter III).

Transitional issues and initial staffing—Moving revenue administration outside the public

service—which is what implementing an RA does—presents huge challenges. Prime among these

is the impact on existing staff. There are many misunderstandings and misconceptions in this area

6 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

and this chapter attempts to explain the pros and cons of different scenarios that arrive at the same

end—a single new entity outside the public service proper (Chapter IV).

Organizational issues—This chapter highlights the most common issues related to organizational

structure, and identifies common solutions to problems based on the experience of other countries

using the RA model (Chapter V).

Operational readiness—When a revenue authority is established, the existing revenue

departments are abolished and revenue administration is normally removed from central oversight

of the public service. For appropriate public sector accountability and transparency to be in place

and respected, the RA will need policies to govern its management actions from the first day of the

coming in to force of the RA legislation. While most of the core program operations will remain

unchanged with the creation of the RA, much of the management policies and practices will be

new. This chapter provides guidance for operating a revenue administration in the RA context,

introduces the importance of the official start date for the RA, discusses advance preparations and

policy development, outlines the role of the Board prior to the official coming-in-to-force of the

new legislation and suggests advice to minimize risk to revenues (Chapter VI).

Project management—The implementation of the RA is a significant effort for any government

and cannot be managed as a marginal activity or on a part-time basis. The complexities inherent

in a decision of this kind dictate the need for a formal project management approach. This chapter

provides an assessment of the importance of using modern project management techniques for RA

implementation. The chapter also introduces a typical, detailed project management plan on RA

implementation for illustrative purposes (Chapter VII).

Communications—Communications could well be the most critical success factor for RA

implementation. This chapter provides an overview of essential communications aspects of the

project and reinforces the idea that the communications messages are a function of the approved

policy choices. It also recognizes the need for tailored approaches to certain stakeholders

(Chapter VIII).

Reform and modernization—The RA is not a goal in itself. The real objective is improved

revenue administration, which requires a program of reform and modernization. In this context,

RA implementation needs to be accompanied by a strategic and comprehensive approach to

integrity (diagnostic process, visibility of actions, code of conduct etc.) and transparency (which

includes published performance indicators and other measures). This chapter discusses the notion

that the RA is not a substitute for reform and that it is really a platform to pave the way for better

revenue administration (Chapter IX).

Information technology—Information technology underpins modern revenue administration

and the move to an RA can pose certain challenges as the existing departments generally have

their own large IT systems. Questions arise as to the extent to which system integration makes

sense and whether more fluid ways can be found to exchange information electronically, while

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 7

respecting statutory provisions. The revenue authority will also need to consider its need for IT

systems that support its new management responsibilities i.e. HR, finance and budgeting. This

chapter reviews key areas and provide advice (Chapter X).

Change management—This chapter provides information on the specific, concrete steps needed

to maximize support and acceptance of a new revenue authority. It focuses on organizations and

people (Chapter XI).

8 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

i. introduCtion and BaCkground to revenue

authorities

1. The idea of establishing revenue authorities (RAs) for tax and customs administration has

been part of a growing trend for more than 20 years towards increased autonomy in the public

sector. The basic principle is that such autonomy can lead to better performance by removing

impediments to effective and efficient management while maintaining appropriate accountability

and transparency.

2. Much has been written about revenue authorities—from case studies on national experience to

analyses that attempt to judge RA effectiveness in reaching reform and modernization goals. These

varied efforts can be of great value to countries as they review whether a revenue authority is the

right solution in the national context.

A. Some Terminology

3. Throughout this toolkit, certain terms are used that, while often commonly understood, can in

fact have a range of meanings. For clarity, the following definitions are offered and will be used.

Autonomy—The degree to which a public sector organization is able to operate independently

from government, in terms of legal form and status, funding and budget flexibility, and financial

and human resources policies.

Accountability—The extent to which roles and responsibilities are clear, authorities are

appropriately delegated, and those so empowered to make decisions are in fact held responsible

for them and their consequences. There can be both individual and organizational accountability.

Governance regime (or model)

1

—The institutional or structural framework that determines the

responsibility, authority, and accountability for a government institution. In the context of a RA,

these parameters dictate the relative autonomy of a given government organization in terms of

government control and of the applicability of public service policies.

Government control—The degree of involvement by central government in decision-making

within the agency, both from a program and administrative perspective.

B. What Is a Revenue Authority?

4. A revenue authority (RA) is simply a term to describe a governance regime for an organization

engaged in revenue administration, where the regime provides for more autonomy than that

afforded a normal department in a ministry.

1

The term “governance” is often used more broadly. The World Bank uses six dimensions to measure governance:

voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule

of law, and control of corruption.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 9

5. While some 30–40 countries have RAs, there is no single governance model that applies

everywhere. Each RA embodies a series of policy choices that determines its autonomy,

accountability and other characteristics. RAs exist along a continuum, with some RAs remaining

close to the civil service while others enjoy greater autonomy. An RA is not an end in itself and

should be a means for implementing reforms and improving performance. If used effectively, it can

be a catalyst to enable broader revenue administration reform.

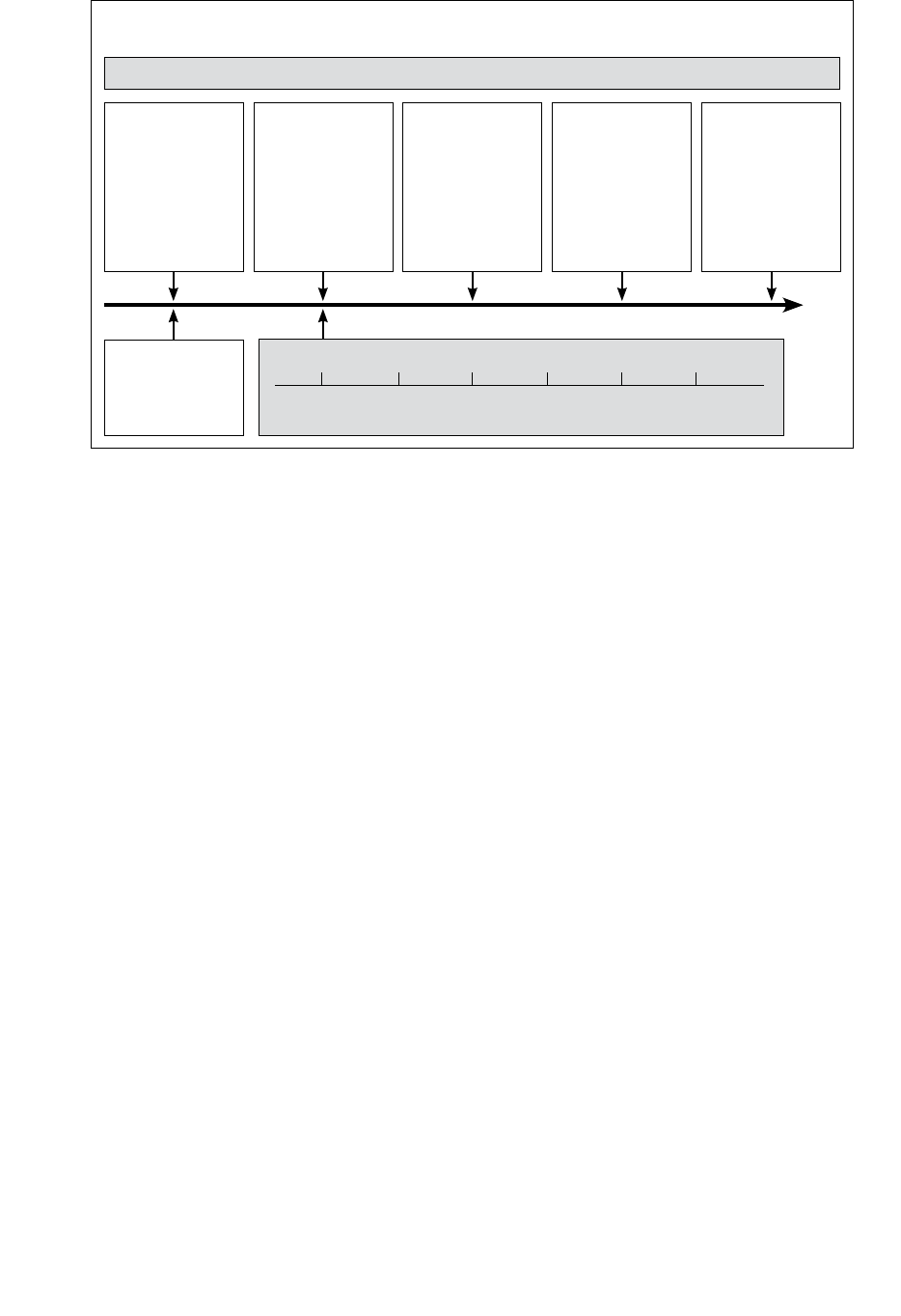

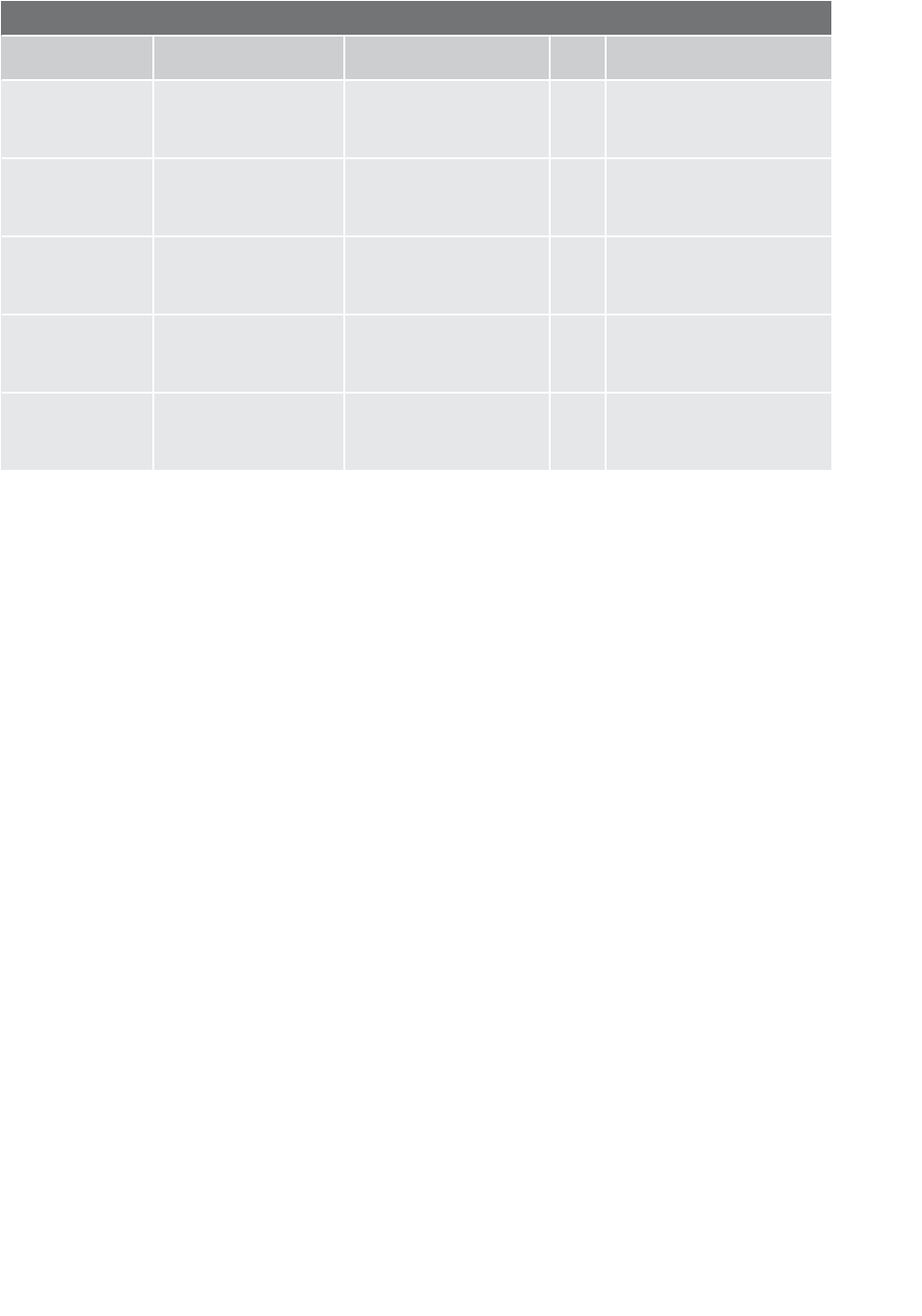

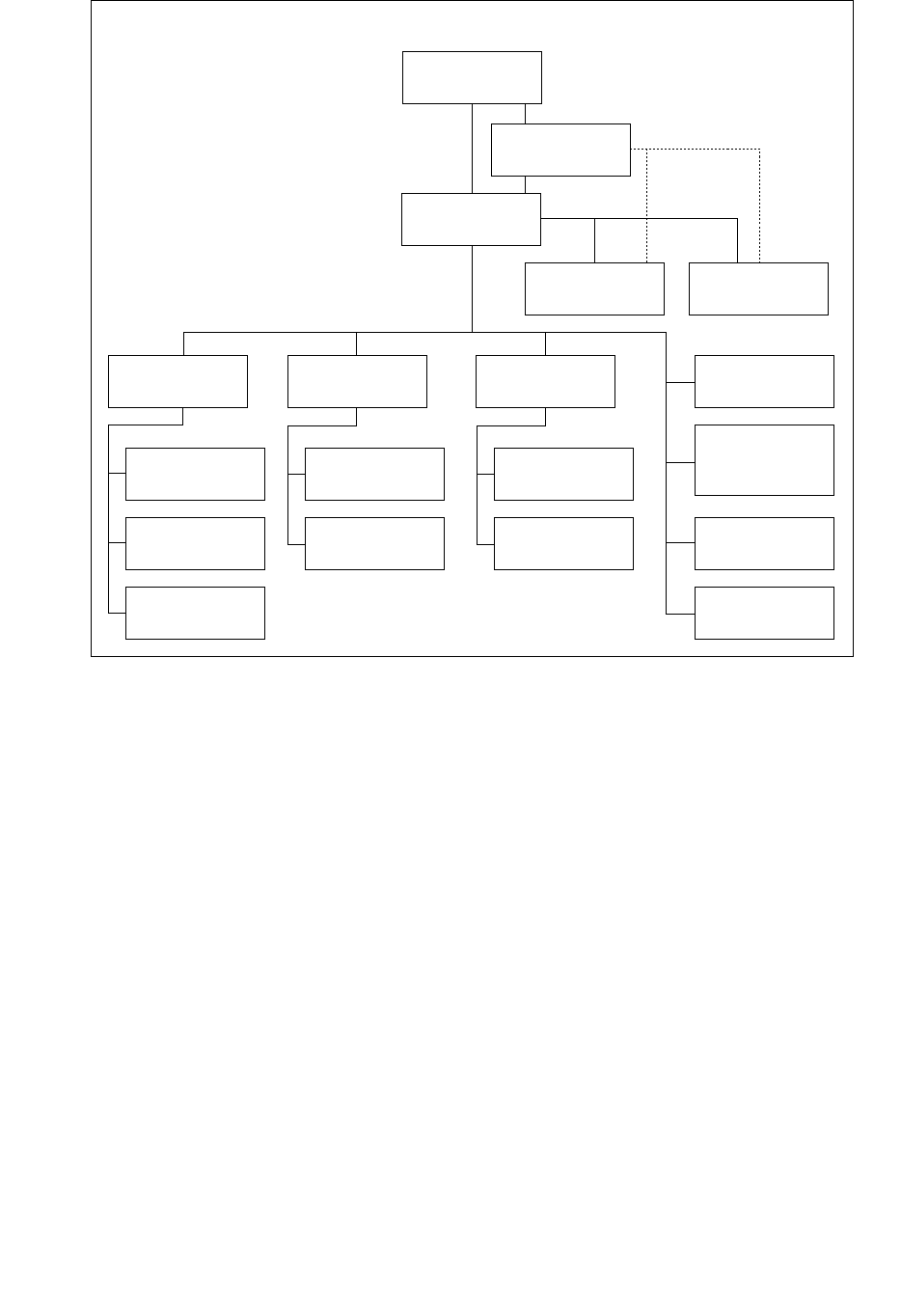

6. Figure 1 provides a depiction of the relation between government institutions and autonomy.

Looking at government functions along a spectrum of decreasing government control and

increasing autonomy, it can be seen that government departments provide the least autonomy, then

semi-autonomous agencies like RAs, then the autonomous agencies and regulatory bodies, then

state owned enterprises, and finally privatized functions. Revenue administrations are normally

either departments of government or semi-autonomous agencies.

7. For many countries interested in establishing an RA, it may be appropriate to adopt a general

orientation of aiming at the middle of the autonomy spectrum for RAs. The shaded box in Figure 1

suggests there is are widely varying degrees of autonomy within RAs themselves. For example,

based on the autonomy granted through the enabling legislation, the revenue authorities in Peru

or Kenya clearly have more autonomy than the revenue authorities in Canada or Mexico.

8. RAs deal predominately with indirect and direct tax administration at the national level, and

usually with customs administration as well. Tax and customs laws include some of the most

intrusive powers of the state, and in no known cases are revenue administrations granted complete

autonomy from government. Rather, they are given “semi-autonomous” status. Their powers are

not too far removed from the control and accountability of elected government, and therefore tax

and customs organizations are likely to always remain public institutions.

FIGURE 1. AUTONOMY AND REVENUE ADMINISTRATION GOVERNANCE

Government organizations – Increasing levels of autonomy

Normal

Department

e.g.

Agriculture

Finance

Semi-

autonomous

agency

e.g.

Revenue

Authorities.

Scientific

Councils

Autonomous

Agencies and

Regulatory

Bodies

e.g.

Central Bank

State-owned

enterprise

e.g.

Broadcasting

Railways

Privatized

organizations

e.g.

air traffic control,

prisons

Examples:

France,

Cambodia,

Norway

Revenue Authorities (by increasing autonomy)

USA Mexico Canada Mauritius Kenya Peru

Australia UK Uganda

10 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

9. The RA has been seen by some as a possible solution to critical problems, such as poor revenue

performance, low rates of compliance, ineffective staff, and corruption. It has often been argued

that an RA can lead to improvements, including better accountability for results, synergies in

administration across the revenue departments, and management based on professional skills and

isolated from external influences. The prospect of improvements in all these areas generally drives

the decision to implement a revenue authority.

C. Making the Decision to Proceed

10. As noted earlier, there is usually a common set of considerations for most countries as they

assess whether a revenue authority is a reasonable option to pursue. The decision is clearly not

taken lightly as the implementation process can consume as much as two years (and often more)

of the time of senior officials and political leaders.

11. An IMF research paper

2

presented a summary table that ranks the reasons that countries themselves

cited in their decision to implement a revenue authority and these findings are presented in Table 1.

12. Many ECCB members will see their own national situations reflected in this chart. Care should

be used though in any rush to decide that a revenue authority is in fact the right solution to the

problems facing existing revenue administration. Before moving to an implementation decision

(and using the balance of this toolkit), governments should consider carefully the following series of

questions and issues:

2

Kidd, Crandall. IMF Working Paper. Revenue Authorities: Issues and Problems in Evaluating their Success and

Failure. May 2006

3

These averages come from a survey of countries with revenue authorities (the survey was part of the IMF Work-

ing Paper mentioned in footnote 1) and reflect the respondent’s own views of reasons for implementing a revenue

authority.

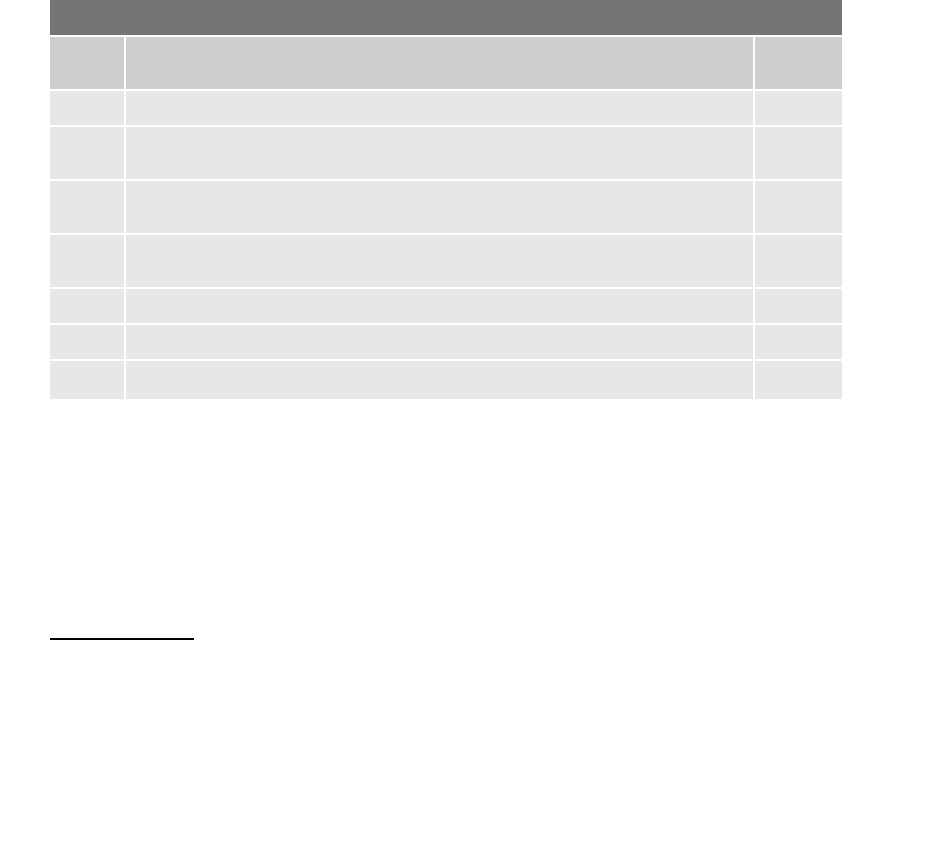

TABLE 1. REASONS (RANKED) FOR IMPLEMENTING A REVENUE AUTHORITY

Rank Reason

Average

Ranking

3

1

Low effectiveness of tax administration and poor levels of compliance 1.8

2

Need for a catalyst to launch broader revenue administration reform (modernized

operations, improved automation, integrated and function-based structures, and so on)

2.73

3

Impediments caused by poor civil service human resources policies (recruitment,

remuneration, promotion, training, discipline)

2.9

4

Poor communication and data exchange among the existing revenue departments

(e.g., income tax, sales tax, customs)

4.21

5

Desire to create “islands of excellence” within the public sector 4.54

6

Perceptions of political/ministerial interference 4.55

7

High levels of corruption 4.67

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 11

Are the problems facing revenue administration known?

13. The problems and challenges facing revenue administration need to be well-documented.

Specific studies or diagnostic reviews should be performed to identify problems and challenges in

capacity, organization, integrity, etc. Such studies can identify reform requirements and frame the

background for consideration of possible revenue authority implementation.

Is there a reform and modernization strategy in place?

14. Many countries have in place formal plans for reform and modernization of their tax and/or

customs administrations. The progress and success of these plans (or lack thereof) is an important

consideration in the RA decision. Also relevant is any broader civil service reform agenda that may

be in place in a particular country.

Is there a risk that creating the RA will overwhelm other reform efforts?

15. The risk exists that the move to a revenue authority can overwhelm all other reform efforts.

It is therefore necessary to make certain judgements about (1) the extent to which creating a RA

is necessary as a catalyst so that reform offers the prospect of a quantum leap in performance

and (2) the extent to which energy spent on creating a RA is likely to detract from reform and

modernization initiatives already underway and dilute potential success.

Are the benefits and downsides of revenue authorities well understood?

16. In some countries, the RA model was adopted with little consideration of the potential benefits

and downsides. In the final analysis, the government’s decision will be based on judgment, rather

than empirical facts, in view of the absence of definitive and scientific data concerning the real

benefits of the RA model.

Are the experiences of other countries relevant?

17. According to the IMF research paper, the two highest priority reasons for initially establishing

an RA are low effectiveness and the need for a catalyst for reform—issues that also tend to be

high priorities for all revenue administrations, RAs or not. The third highest ranked reason was

removing impediments caused by poor civil service HR regimes. The remaining reasons (including

perceptions of political interference and high levels of corruption) are clustered closely together

with a much lower average ranking.

18. The objectives of any revenue administration reform and modernization program are very

similar to the reasons for which RAs are established. This underlines the complexity of the

decision whether an RA is the best option for the government to pursue. In many countries, low

effectiveness and the need for a catalyst are indeed relevant as are the difficulties created by the

12 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

current civil service regime. The countries that chose the RA model did so precisely to overcome

these problems. However, many countries have introduced reform programs to address similar

problems without resorting to the more radical solution of a semi-autonomous agency. Again, the

decision becomes a judgment as to what will work best.

Is a lengthy timeframe acceptable?

19. Experience has shown that successful implementation of a revenue authority can take

anywhere from 12 to 18 months, or longer. It requires a dedicated project team, competent

officials assigned on a full-time basis to the effort, liaison with many areas of government

(e.g. justice regarding the legislative agenda of government and priority given to RA enabling

legislation, the civil service agency regarding staff and transition, the budget office regarding

resources, etc.) as well as professional advice that may not be available in-country.

20. Perhaps most importantly, the implementation of a RA consumes senior management time and

energy. This is a major undertaking which should not be underestimated, as these senior managers

are the same ones who will be responsible for maintaining operations and meeting revenue targets

during the RA implementation period, and who will have continued responsibility for all major

reform and modernization initiatives at the same time.

Are requisite skills and other resources available?

21. Will the government be able to meet any increased salary commitment and operational

funding that is typical of many revenue authorities? One of the features of many revenue

authorities is that the salaries paid to employees are higher than those in the mainstream civil

service, and that the operational funding requirements of the RA are often better satisfied. The

government will also have to consider any increased costs in these areas in terms of their impact

on the rest of the civil service, and in terms of the impact on its civil service reform strategy.

22. With the shift to a revenue authority, the tax and customs departments leave behind the

existing government framework for human resources, budget, and procurement; in fact, for all

aspects of management and administration. Normally, the RA enabling legislation establishes a

board of management that will assume these responsibilities. The board includes government

and private sector representatives and this is designed to inject private sector best practice into

the management of the new RA. In some countries, concerns have been expressed about not

only the quality of potential board members but also their ability to act impartially and in the

best interests of the RA. The issue of political influence with respect to the board would also

need to be assessed.

23. Finally, implementation itself requires particular skills. Many countries have benefited from

the assistance of foreign consultants in developing and preparing for RA implementation. This can

involve significant resources, and support from the donor community.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 13

Is the government prepared to deal with possible labor relations upheaval in a move to

a revenue authority?

24. Unless a government decides to move all existing staff over to the new RA, there is usually a

multitude of issues arising from the treatment of existing staff that will garner great interest from

the union or staff association. From what happens to staff to the status of the union as bargaining

agent, there are many issues where the government’s desired outcomes will likely not generate

union support. This can often be mitigated by early engagement with the union. Nevertheless,

there is a political, policy and tactical decision to be made by government on the extent to which

they want to engage the union on this particular issue.

25. Another issue is the extent to which the government would be able to meet the increased

salary commitment and operational funding that is typical of many revenue authorities. One

of the features of some revenue authorities is that the salaries paid to employees are higher

than that of the mainstream civil service and that the operational funding requirements of the

RA are usually met.

Are there any reasonable and practical alternatives?

26. Many governments are looking at the overall state of the civil service and the rules that

underpin all aspects of government administration to determine whether more flexibility is

needed, is possible and could be granted. In fact, recent studies of revenue administrations for

countries that do not employ the RA model suggest that increased autonomy is more and more the

norm, reflecting an overall trend in this direction across governments. Countries will need to be

sure that the RA model is actually needed to obtain the level of autonomy desired.

Are the conditions for success and sustainability present?

27. There is little point in proceeding with the establishment of a revenue authority if conditions

for its success and sustainability into the future are not present. The critical success factors for a

revenue authority can be summarized as follows:

Strong political support at the highest level.•

Senior management commitment and determination.•

The development of a sound policy framework.•

A pro-active communications strategy, involving the parliament, the public, employees, and •

other stakeholders.

An understanding by all that the RA is a platform only, a pillar to support a full revenue •

administration reform and modernization program, which must proceed at the same time.

The provision of adequate resources.•

A strong project management approach for implementation.•

A committed donor-partner.•

14 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

D. Conclusions Reached about RAs

28. The IMF paper referenced earlier as well as other literature on the subject of RAs generally

suggest a few words of caution on the subject. Conclusions from these analyses can be summarized

as follows:

Establishing an RA should not be viewed as a panacea—creating an RA may be expensive, may •

take a long time, and may not actually improve revenue administration effectiveness;

Before considering any particular governance model, revenue administrations should clearly •

identify and articulate problems and deficiencies, and consider strategies for reform and

modernization based on international best practice. Only then should a full assessment be

made of the extent to which the RA governance model might satisfy the problems and reform

strategies identified;

Whatever the governance model, it must be recognized that political commitment is of •

the utmost importance in establishing and sustaining a professional and effective revenue

administration;

The RA model alone does not lead to improved effectiveness and taxpayer compliance—its •

establishment must be coupled with a serious commitment and plan for reform.

E. Revenue Authority Websites

29. Countries considering a revenue authority may want to review information from countries

that have already implemented a revenue authority. For ease of reference, a list of selected revenue

authority websites follows.

Botswana Unified Revenue Service: www.burs.org.bw

Canada Revenue Agency: www.cra-arc.gc.ca

Guyana: www.revenue_gy.org

Kenya Revenue Authority: www.kra.go.ke

Malawi: www.sdnp.org.mw/mra

Rwanda Revenue Authority: www.rra.gov.rw

Peru: www.sunat.gov.pe

Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore: www.iras.gov.sg

South Africa Revenue Service : www.sars.gov.za

HM Revenue and Customs: www.hmrc.gov.uk

Zambia Revenue Authority: www.zra.org.zm

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 15

ii. PoliCy ChoiCes

A. A Framework for Policy Choices

30. A country needs to have a framework to consider the policy choices it must make when

establishing a revenue authority (RA). In recent years, it has come to be accepted that this

framework will encompass the following components: degree of autonomy; governance

framework; accountability; and scope.

31. In almost all cases, the framework spans a range of possibilities from which the government

must choose just one. It helps when the government has a general end-state in mind, such as a

stated desire to have a RA “in the middle” in terms of autonomy, or “similar to country X” with

respect to the governance framework, levels of efficiency and professionalism, etc.

B. Degree of Autonomy

32. The range of possibilities for the following specific areas needs to be assessed:

Legal form and status—from an agency relatively close to a normal government organization, to

a corporate body with considerable independence.

Funding—from normal funding via parliamentary appropriations to direct retention of a

percentage of collected revenues.

Budget flexibility—from limited flexibility to the complete flexibility of a one-line budget.

Financial policies (such as accounting, asset ownership and management, procurement)—from

a situation where the RA is subject to standard civil service laws and regulations, or as determined

by “corporate body” status (i.e. not part of the government’s accounting entity).

Human resources—from being within the civil service control framework, to outside it.

Operational autonomy—from a situation where the minister has day-to-day authority to one

where there is no involvement on the part of the minister in operational decisions.

C. Governance Framework

Role of the minister of finance—from direct supervision of the authority by the minister, to a

more limited role such as appointment of the board or CEO only.

Role of the board—from advisory to fully empowered in legislation to take management

decisions.

Role of commissioner general—from a coordinating role only, to full responsibility for revenue

operations with all vested powers from revenue laws.

16 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

D. Accountability

Reporting to the government and parliament—from being part of normal general government

reporting, to the need to follow special requirements specified in legislation.

External audit—from being a legislated responsibility of the auditor-general, to the RA or its

board selecting the external auditor as it sees fit.

E. Scope

33. This refers to the scope of taxes and taxing agencies to be included. Usually, the RA includes

the administration and enforcement of all direct and indirect taxes at the national level, and

customs (and trade) administration. The RA may also include the collection of local taxes or fees

and social taxes or levies, as well as the collection of social contributions.

F. Analytical Matrix for Policy Choices—a Module

34. Below is an analytical matrix for considering and recording the policy choices related to RA

implementation. Management at the most senior level (up to Permanent Secretary) will need to

participate in the policy choices at the level set out in the matrix (Table 2).

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 17

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Degree Of Autonomy)

General

area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Legal form and status Mandate The mandate of the RA needs to be clear and unequivocal. Almost all RAs have the

mandate to assess and collect taxes and duties and administer and enforce the

revenue laws, and many have the further mandate to provide advice about the tax

laws to the minister of finance.

In addition, most RA laws set out the specific powers and functions or

responsibilities of the RA.

Corporate character Most RAs are described as having a corporate character (being a body corporate or

having “legal personality” and meaning they can sue and be sued).

All have authority to own assets. About 50 percent of RAs have the authority to

borrow, although in 40 percent of those cases the prior approval of the minister of

finance is required.

Relationship to Minister of

Finance

Essentially, the RA’s relationship to the government is normally through the minister

of finance who is accountable to parliament for RA performance .

Most governments do not allow RAs to move too far away from central oversight—

most RA laws assign the minister of finance at least general supervision and

oversight of the RA.

Relationship to public service Most RA legislation makes clear that RA is outside the normal ambit of the public

service especially with respect to HR laws, policies and regulations. In addition,

RAs are not usually limited by public service rules and regulations regarding

budget flexibility, procurement and asset management. One area where RAs often

remain part of the PS is with respect to accounting policy and being part of the

government’s accounting entity.

18 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Degree Of Autonomy)

General

area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Funding Funding basis There are two basic means—(1) provision of a standard parliamentary

appropriation using the normal public expenditure management (PEM) and budget

decision processes of government or (2) inclusion of a percentage-of-collection

funding formula, or guarantee, in the RA legislation. This can also be referred to as

a collection fee.

Percentage-of-collection funding formula can insulate the RA from the vagaries

of a suboptimal budgeting process (if that is the case), it can provide greater

certainty and reliability, and it can be structured to provide incentives for improved

performance. Arguments against the use of such a formula include the fact that

many factors that impact revenue collections, not just the efforts of the revenue

administration e.g. general performance of the economy and tax policy changes.

70 percent of RAs are funded by appropriation (half of these include the possibility

of performance incentive payments based on achieving revenue collection targets).

About 30 percent are funded based on a percentage of tax collection although at

least some of these are still controlled by the Minister of Finance.

Public service policies Budget flexibility Treasury or the budget office in the finance ministry sets the rules and procedures

for all government organizations—primarily the ability to move funds across budget

lines (such as capital versus recurrent expenditures, salary versus non-salary

expenditures, and so on). The RA needs to be able to respond quickly to changing

demands in areas such as enforcement, or service, and be able to make trade-offs

between budget lines. Almost all RAs have the flexibility of a one line budget and

most include some provision for the carryover of unused funds.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 19

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Degree Of Autonomy)

General

area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Note: in all areas

where the Board

becomes responsible

for policies that were

previously in the public

service domain, it will

be incumbent on the

Board to ensure that

all principles of public

administration (e.g.

transparency) are

respected.

Fiduciary responsibilities The fiduciary responsibilities of a public institution: accounting practices, payment,

chart of accounts, accounts receivable, invoicing, contracts, etc.

Overall HR regime, including:

recruitment

remuneration

performance assessment

conditions of work

career development

discipline

termination/ demotion

pensions

RAs usually have significant authority here as management efficiency and

effectiveness can be improved by getting out from under an outmoded regimen of

public service human resources rules and regulations.

Boardís sphere of responsibility for human resources would normally include the

overall human resources regime for the RA; the salary scheme for employees and

positions; the performance assessment scheme, including performance-related

incentives; all matters relating to conditions of work, including hours of work and

overtime arrangements; career development/progression; standards of discipline,

and sanctions for breaches of discipline including termination or suspension;

employee termination or demotion for poor performance; employment-related

expenses or other terms and conditions of employment, and, pensions.

Purchase of goods and services

Asset management

Purchase of goods and services in the public sector is founded on the principles

of fair and open competition, value for money, and transparency. Public sector

procurement must also reflect trade agreements and other complex policies.

Most RAs have the right to own assets and clear policies on asset management,

including such areas as life-cycle management, lease versus purchase, space

optimization, asset disposal, and the like are usually in place.

20 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Governance framework)

General area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Role of Minister of

Finance

Degree of control and

supervision

Role of the minister of finance regarding the control and supervision of the RA,

budget approvals, and other legal aspects of the RA is critical. This is an essential

component of how much authority is exercised by the government.

Role in CEO, Chair and Board

appointments

Other levers where government exercises its control include the approval of the

board, its chair, and the CEO. Clearly, the government is the “shareholder” of the

corporate body (the RA) and therefore needs to have a say in the appointment of

those who will govern that body. In virtually all RAs, the chair of the board and the

CEO are named and appointed by the government, with this role often assigned to

the minister of finance

.

Directive power Many government institutions that have been established as corporate bodies,

including RAs, include a provision for the minister to issue a directive to that

corporate body. This kind of provision allows the government as the effective

shareholder to direct that some particular action be done. Any such direction

requires maximum transparency, usually through publication in a country's official

gazette. The argument in favour of these kinds of mechanisms is that they maintain

a certain amount of executive level authority and accountability without materially

affecting the autonomous nature of the RA, since the expectation is they would be

rarely used

.

Role of the Board General Some 75 percent of RAs are constituted with an empowered management board

whose functions and powers are set out in the law and form an essential part of the

organization's governance framework.

Such boards are almost always prohibited from involvement in the operational

execution of the tax and customs laws, and from access to any information about

individuals or corporations obtained as a result of the administration and enforcement

of those laws. To do otherwise would place any (private sector) members of the board

in an obvious and untenable potential conflict of interest situation.

Powers and functions Powers and directives need to be specified in the enabling legislation and typically

include the following:

• oversee the administration, management, and organization of the RA;

• oversee the management of resources, services, property, personnel, and

contracts;

• approve the strategic plans and the budget of the RA;

• approve the annual report;

• establish policies to be followed (particularly important where public service laws

and policies will no longer apply);

• establish by-laws for the functioning and operations of the board,

• internal audit.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 21

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Governance framework)

General area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Functions of chair All RA legislation provides list of functions of the chair (standard). Chair will normally

preside over the boardís meetings and exercise the powers and functions as

prescribed by by-laws established by the board under its legislated authority.

Role of the Board Selection of members In the interest of ensuring sufficient capacity on the board, all members must have

the experience and knowledge required for discharging their functions, normally in

finance, accounting, taxation, public administration, law, or some other related field

Ex-officio members Board requires a mixture of skills and experiences in order to be effective. May be

necessary to include certain government representatives on the board. In order to

ensure autonomy at the same time, these positions are usually based on the notion

of fixed ex-officio, or non-voting, appointments. This respects the principle that all

(voting) members of the board are required to act strictly in the best interests of the

organization, and not represent the interests of some other constituency.

In the context of corporate governance, there is a debate as to whether the CEO

should also be a member of the board. CEO of the RA has a critical role to play and

has an important relationship with the board, as well as with the minister of finance

in terms of the revenue laws.

Size of board Considerable debate has also taken place concerning the optimum size for

corporate boards. Boards of 7 to 12 members are now being considered optimal in

terms of the efficient and effective functioning of corporate boards. Larger boards

than this are considered unwieldy; smaller ones are felt to be too narrow and

tending to lack comprehensive skills.

Remuneration of board

members

Many countries have guidelines for the remuneration of part-time board members.

Statutory powers and

obligations

All the powers and obligations related to the revenue laws (such as the power to

assess taxes, make a customs determination, issue interpretations, impose or waive

penalties, and so on) are usually given to the CEO through the enabling legislation of

the revenue authority, who in turn delegates them to other senior officials and staff.

22 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

TABLE 2. ANALYTICAL MATRIX FOR POLICY CHOICES

(Accountability)

General area Specific Issue Discussion Final Policy Decision

Audit External auditor An RA must have external audit. There are two choices for external

audit—either the board appoints the external auditor, or the auditor

general of the country, which reports to parliament, is named the external

auditor for the RA. Most RA legislation names the auditor general of the

country as the external auditor for the RA

Reporting to parliament

Strategic plans, annual reports Providing formal reports to parliament is one means of ensuring

accountability to both the parliament and the executive. The two most

common forms of reporting are through the annual corporate plan and

budget (a look ahead at what the RA plans to do in the coming year) and

the annual report (a look back at what was accomplished in the year

past). Such documents provide valuable information to the government

and the parliament, to ensure transparency. Virtually all RAs have some

form of reporting to parliament (via the minister of finance) as part of

their RA legislation.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 23

iii. legislative issues

Introduction

35. This chapter discusses the need for separate enabling legislation, the importance of taking

and recording policy decisions as a first step, the relationship of the enabling legislation to other

laws, the typical structure and components of RA enabling legislation, and the importance of

the parliamentary timetable for legislative approval. This chapter also includes a checklist for

developing the RA legislation. Finally, the chapter includes an appendix (located at the end of the

toolkit) which discusses specific country RA laws and provides a commentary on selected laws as

well as a copy of or internet reference for them.

A. The Need for Enabling Legislation

36. All countries which have established a revenue authority have enacted specific legislation

to provide necessary authorities. In general, these laws have not had any particular difficulty in

being passed by the respective parliaments. There are now some forty revenue authority laws in

existence, and many of these can be accessed via the internet.

3

37. Some of the most widely referenced revenue authority laws are those based on the Anglo-

Saxon or British administrative law system. These would include many that were developed and

passed in the early 1990s such as Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, as well as a number that have

come later such as Zambia, Mauritius, and Botswana. This group of laws all follows a consistent

pattern. Other laws can also be useful for reference, such as those from Canada, Italy, Peru, the

United Kingdom—however these are in some ways very specialized pieces of legislation with

many features that may not be relevant on a global basis. For a further discussion of RA laws, see

appendix 1 to this toolkit: a commentary on specific revenue authority laws.

B. Reflecting the Policy Choices

38. Chapter II deals extensively with the issue of policy choices for the revenue authority.

39. Legislation needs to follow the policy decisions, not lead them. It is therefore imperative to

develop a comprehensive policy framework (reflecting all the policy decisions) that can serve to

inform and guide the development of the enabling legislation.

40. The policy framework should be the basic document from which all other documents or

requirements are developed. This includes briefing notes for Cabinet, internal and external

communications strategies, consultation strategies, and of course the legislation itself. The policy

framework will be the single most important item for the legislative drafting team.

3

The easiest way to access RA laws is to conduct a google search,, e.g. “Kenya Revenue Authority Act” to locate the

best website.

24 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

C. Working with the Ministry of Justice

41. The Ministry of Justice has a key role to play in drafting all legislation, and the enabling

legislation for establishing a revenue authority is no exception. However, in the case of the RA,

the Ministry of Finance is normally the policy department and charged with making all the policy

decisions that need to be reflected in the law.

42. The ministry of justice needs to give advice on many aspects of the law—interrelationships

with other legislation, key wording, drafting style and content, and many other issues. As noted,

the key guidance for justice ministry officials will be the approved policy framework.

D. The Relationship with Other Laws

43. The revenue authority enabling legislation will be an administrative law and will need to

support and fit in with other key administrative laws. There are two main categories of such laws:

revenue laws; and public service legislation.

Revenue Laws: The main function of the revenue authority will be to administer and enforce

the revenue laws. These revenue laws will need to be listed in a separate schedule to the enabling

legislation. The government will need to be able to add to or subtract from this list (normally via

Regulation) in order to reflect changes in the tax policy of the country.

Public service legislation: One of the key features of all revenue authorities is that they

effectively move out of the ambit of the public service proper. A specific decision needs to be

made as to the extent to which the RA might remain subject to certain public service legislation.

The main areas that need to be looked at in this regard are human resources, procurement, and

finance and accounting.

44. In terms of human resources, it is likely that the RA will no longer be subject to any

broad public service laws affecting recruitment, promotion, discipline, and training. These

functions will be governed by policies implemented by the RA’s Board. Furthermore, where

separate legislation exists to guide and inform labour management relations in the public

service, this is unlikely to continue to apply to the new revenue authority. The new RA

is more likely to fall under broader national legislation that deals with corporate or other

entities generally.

45. Procurement is another area that often has a specific legislative or regulatory framework for

public service departments. In some cases, this public service legislation continues to apply to

the RA. This is a policy decision, of course and the enabling legislation must clearly set up the

legislative relationship if any to reflect approved policy. Finally, regarding finance and accounting,

the policy decision will determine what has to be said in the enabling legislation and what other

laws if any need to be referred to.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 25

E. Structuring the RA Law

Introduction

46. The enabling legislation reflects dozens of critical policy choices and is tailored to the specific

needs of the country in question. It can be modeled on existing RA laws but can also feature some

significant enhancements.

47. Explanatory notes are normally developed for each article of the draft legislation. These notes

serve to provide background, for example as to why the article is necessary, what international

norms might apply, the experience of other countries, etc. Such notes can be particularly useful for

officials and ministers during the parliamentary review process.

Typical structure

48. Laws to establish revenue authorities tend to follow a common model, usually the one based

on the Anglo Saxon system. The key elements of these laws (referred to as PARTS and identified

with roman numerals) and what they typically include are set out below.

49. Part I—Preliminary items: This Part usually includes a title (or short title) for the legislation

as well as a section specifying the basis upon which the law is to be interpreted. In many case,

especially in more modern RA laws, this Part often includes a number of definitions.

50. Part II—Powers and functions of the Authority: This Part actually creates the Authority at

law (as a body corporate) and establishes its responsibilities at the broadest level. “Authority” is

a generic term which includes all aspects of the organization—its governance structure—Board,

Commissioner General (or CEO) and employees. This Part normally makes it clear that the

Authority will operate outside the normal ambit of the public service.

51. Part III—The board of management: This Part establishes the Board of Management of the

Authority, sets out its powers and functions, deals with appointment and termination of the Board

members and Board chair and provides parameters for the operations of the Board including

creation of Board committees (in some modern laws, these parameters are included in regulations

rather than the legislation itself).

52. This Part also serves to create the position of Secretary to the Board of Management.

53. Part IV—Staff of the Authority: This part establishes the Commissioner General as the CEO

of the revenue authority, and may also establish the position of Deputy Commissioner General. It

provides authority for the engagement of staff by the revenue authority on terms established by the

Board.

54. This Part may also be used to deal with general issues of confidentiality (except for

confidentiality as applied to Board members) and other issues related to staff such as pensions.

26 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

55. This Part would also be used to establish the idea that the Commissioner General can delegate

his or her powers under the various revenue laws to other members of the revenue authority.

56. Part V—Financial provisions: The RA will be the prime revenue collection agent for the

government. This part of the legislation clarifies how the revenues are collected and accounted for,

sets out how the authority will be funded and financially account for its expenditures.

57. This Part will also deal with reporting (to Parliament) in terms of strategic or business plans and

annual reports. It will also deal with accountability in general, and with internal and external audit.

58. Part VI—Transitional provisions: This is a critical part of the legislation as it deals with the

actual shift to the new organization. It covers such matters as vesting of assets and liabilities in

the new organization, operational requirements related to the launch of the RA, and perhaps most

importantly, initial staffing. These issues are discussed in full in Chapter IV.

59. Part VII—Consequential amendments: This Part deals with consequential amendments

to the revenue laws—for example to deem references to the head of Customs or the head of the

tax administration to be a reference to the new position of Commissioner General of the RA. In

addition, other consequential amendments to various laws may be required—for example, to

remove the customs or tax departments from the schedules to certain public service laws, or to

add the revenue authority to other schedules.

F. Managing the Parliamentary Timetable

60. Even if non-controversial, the revenue authority enabling legislation can take significant

amounts of time to work its way through the parliamentary process. In fact, the duration of time

from tabling the legislation to its passage ranges from two to six months, depending on the priority

assigned by parliament.

61. Governments need to be able to explain to parliamentary committees the reasons they need to

create the revenue authority, the expected results in terms of improved performance, and the exact

requirement for each article in the law. Many countries develop detailed explanatory notes for each

article, section and sub-section for use in discussions with parliament.

62. In planning the implementation of a revenue authority, governments need to factor in the

various dimensions of parliamentary approval, and make an early start on negotiations and

discussions to ensure timely passage of the enabling legislation.

G. Checklist for Developing RA Draft Legislation—a Module

63. Table 3 provides a checklist for those countries developing enabling legislation to establish a

revenue authority. In order to prepare for developing draft legislation, the specific policy decisions

made can be summarized against a rough plan for the legislation so as to ensure a comprehensive

law is developed that can give expression to all the decisions made.

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 27

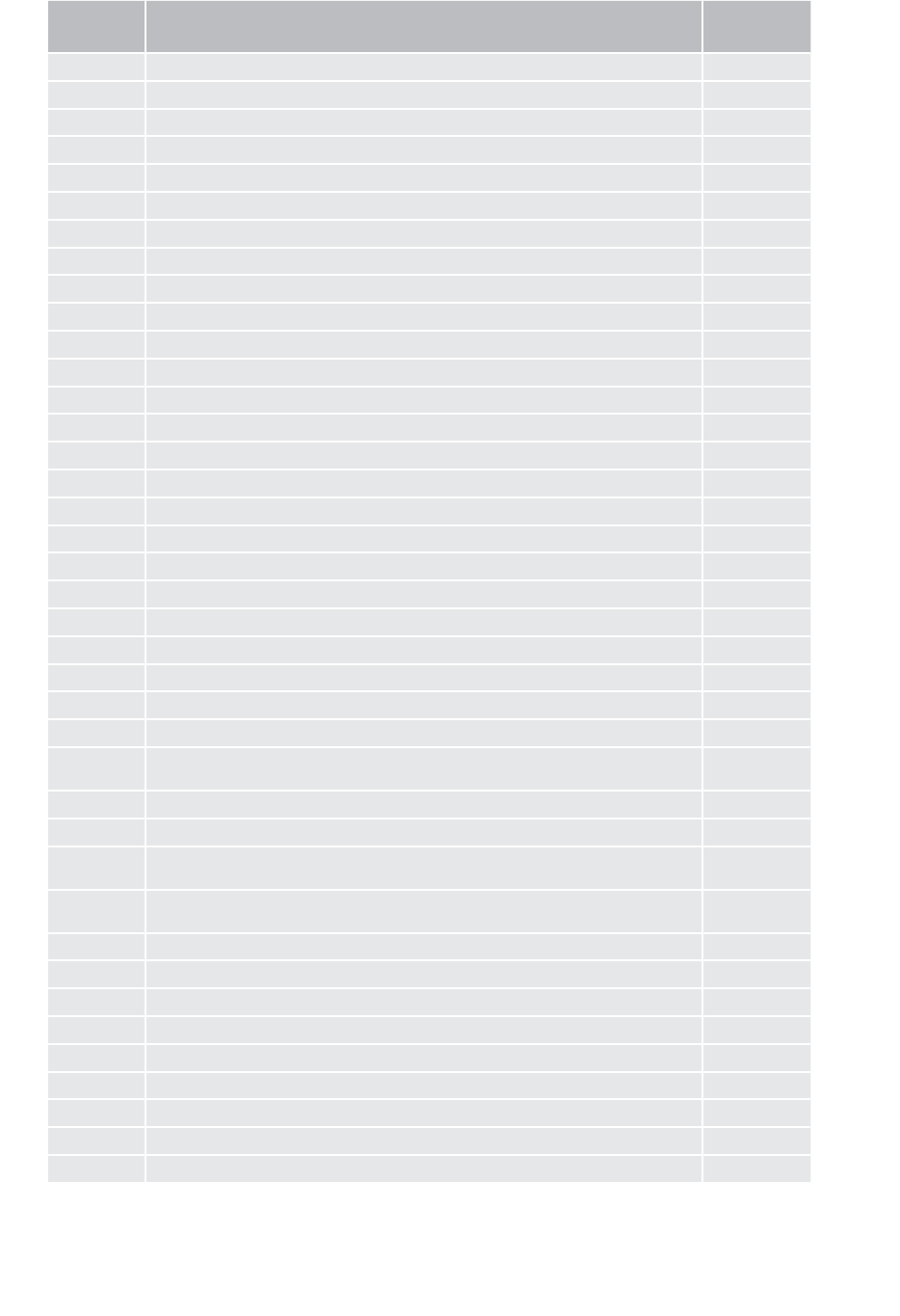

TABLE 3. CHECKLIST FOR RA LEGISLATION

Subjects included

Summary of related

policy decisions Checklist questions

PART I–Preliminary Title, interpretation,

definitions

(to be completed based

on policy decisions

made)

Have all necessary terms been defined?

Are definitions consistent with revenue

laws?

PART II–Powers

and functions of the

Authority

Powers and

functions of RA

Are relationships with other laws clear?

Has the legal nature of the RA been

clarified?

Have all policy decisions been reflected in

the law?

Is the HR regime clear?

PART III–The board of

management

Powers/functions of

board, appointment,

confidentiality

Have all necessary provisions concerning

the board been included?

Should procedural issues be in the law, or

in regulations?

PART IV–Staff of the

Authority

Appointment of CG

and staff

Are appointment authorities clear?

Has authority to delegate powers been

provided for?

PART V–Financial

provisions

Finance, accounting,

audit and reporting

Has the financial and budget regime been

included?

Will the RA be within the government

“accounting entity” or outside it?

PART VI–Transitional

provisions

Vesting of assets,

legal proceedings,

initial staffing

(See Chapter IV)

PART VII–

Consequential

amendments

Impacts on revenue

laws, and other

public service laws

Are references in revenue laws being

changed?

Is it clear which public service laws will

apply and which will not?

28 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

iv. transitional Provisions

Introduction

64. The previous chapter dealt with all the issues related to the enabling legislation for establishing

a RA with the exception of transitional provisions which are dealt with in this chapter. Transitional

provisions are those elements of the enabling legislation that provide the needed authorities

through the period of the actual transition from departments of government to a revenue authority.

This chapter discusses transitional issues in general, and provides advice for obtaining necessary

legislative authority.

Why are transitional provisions necessary?

65. Each of the forty or so revenue authorities established since the late 1980s take their mandate

and scope from the existing tax and/or customs departments. These departments already existed

within the framework of the public service as traditional departments of government before any

notion of a shift to a revenue authority.

66. The creation of a revenue authority usually brings the tax and customs departments together

(if even in a limited way) and moves the RA outside the framework of central government, largely

as it relates to human resources and financial management.

67. The RA does not take on a completely new set of activities and responsibilities—rather,

it assumes those that had previously been the purview of the existing tax and customs

departments. These departments have a legal basis for their existence, a full complement of

staff and any number of ongoing legal commitments (e.g. contracts ). In order to provide for

seamless operations during the transition from regular departments to a semi-autonomous

revenue authority, the enabling legislation normally needs transitional provisions to deal

with these situations. Transitional provisions, by definition, are either one-time or short-term

authorities that enable a smooth transition to occur. There are sometimes misconceptions and

misunderstandings related to transitional issues where an RA is being implemented, often

caused by poor communications.

When are transitional provisions typically needed?

68. There are a number of aspects in establishing and implementing a RA that need to be

addressed through transitional provisions in the legislation. For example, the effective

date for the first day of operation of the new RA (often called Day One), where the former

departments cease to exist and the new RA becomes fully operational, is a critical component

of the transition. Many countries have also found it necessary to secure authority through a

transitional provision for the appointment of the Board Chair, the Board and Commissioner

General before Day One so that decisions on the human resource and financial management

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 29

framework can be taken, and the framework put in place in time for Day One. This also

allows the individuals selected to be directly involved in key decisions about the structure

and policies of the new RA. Other areas to be considered include the vesting of assets,

management of taxpayer affairs, and the carryover of lawsuits and other legal proceedings,

including employee grievances.

69. Perhaps the most important and indeed most complex part of the transition is initial

staffing of the newly established RA, as the approach selected reflects the objectives of the

government in setting up the RA and has a significant impact on the existing employees in the

tax and customs departments.

70. The next section of this chapter will explain transitional provisions—with the exception of

initial staffing—in more detail. Given its importance and complexity, initial staffing will be dealt

with in its own section.

A. Transitional Provisions—Excluding Initial Staffing

Day One of the new RA

71. The enabling legislation passed by the legislature will usually provide for two distinct dates:

first, the date on which the new law is assented to by parliament, and on which certain aspects

of the enabling legislation become active (such as certain transitional provisions); and, second,

the date on which the full law will come in to effect (or come into force), often referred to as

Day One, the day that the new RA becomes fully operational and accountable for administration

and enforcement of the tax and customs statutes. The period of time between parliamentary

assent and the full coming into force of the law can be as long as 6 months or more.

72. For the new RA to be fully ready for Day One operations, a great deal of preparation and

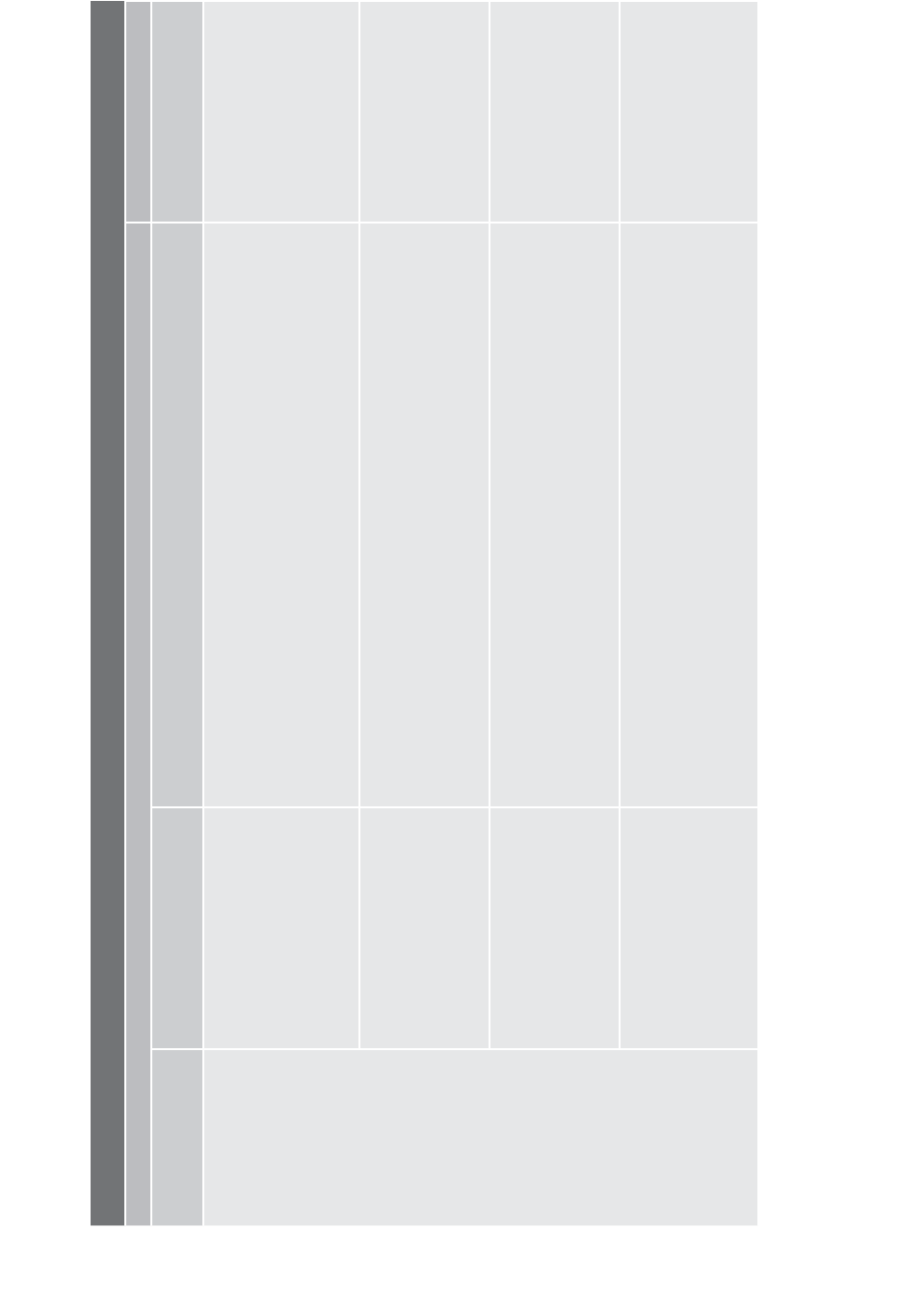

prioritization is necessary. Table 4 identifies five key features of revenue administration where

decisions have to be made and development work undertaken before the coming into force of the

legislation to ensure a successful RA launch on Day One.

73. For each of the five features of the RA, the table outlines where responsibility lies before Day

One, the extent of the work, preparation and the nature of decisions needed and finally, where

responsibility will lie after Day One.

Appointment of the Board Chair, Board and head (CEO) of the RA—before Day One

74. The enabling legislation should allow for the early appointment of the key positions in the new

RA, namely the Chair-to-be of the Board, members-to-be of the board and the head-to-be of the

new RA (most often called Commissioner General or Director General). Often the Secretary to the

Board would be included in these early appointments since much of what needs to be put in to

place must be presented for the Board’s approval.

30 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

75. This group assumes responsibility for all the preparations needed for the coming in to force of

the RA. Work needs to begin directly following parliamentary assent on the range of new policies

that will be reviewed and approved by the Board (their approval is normally “banked” or approved

pending the coming in to force of the legislation during the transition period and formalized on

Day One), on the organization structure and position descriptions and on the approach to initial

staffing and its subsequent implementation.

Vesting of assets and liabilities

76. All assets and liabilities of the existing revenue departments except as may be specifically

designated by the Minister would normally become assets and liabilities of the RA. This would

include property, debts, contracts and other engagements. It will be critical for a complete

detailing of the asset and liability position of the departments to be prepared and ready for early

review by the Board of Management.

Actions and proceedings pending against the departments

77. It is likely that the existing departments will have a number of actions pending against their

organizations and lawsuits, staffing appeals and grievances are some examples. The enabling

legislation needs to provide for continuity for these proceedings to carry on, whether administratively

or in the courts. The RA assumes all responsibility for responding to and dealing with these actions

and a detailed inventory should be prepared for the information of the new head of the RA.

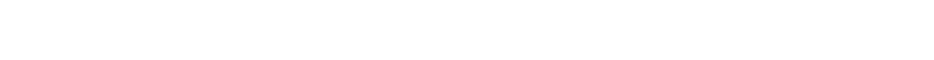

TABLE 4. PREPARATION FOR TRANSITION TO THE RA

Features of revenue

administration

Responsibility in old

regime (before day 1)

Preparation or decision

required

Day 1 Responsibility in new regime

(after day 1)

1. Authorities and

powers

Tax + Customs depts.

(as per revenue laws)

New instrument of

delegation , new policy on

delegation of authority

RA

(as per enabling legislation

and revenue laws)

2. Organization Tax + Customs depts.

(as per revenue laws and

government decisions)

Organizational structure,

position descriptions,

statements of qualification

RA

(as per Board of Management

decision)

3. Funding Government decision

(as per appropriations for

Tax + Customs depts.)

Accounting and financial

cross-walks , new joint

budget

Government decision

4. Policies (e.g. HR) Public service policies

and/or standards, or Tax +

Customs depts. policies

New policies tailored for

the RA to be developed and

approved by Board

RA

(as per Board of Management)

5. Initial staffing Tax + Customs depts. Approach to be determined,

employees advised, staffing

completed

RA

Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010 31

B. Transitional Provisions—Initial Staffing

The human resources framework

78. In most cases, the existing tax and customs departments are part of the formal public service of

the country in question. As such, they are governed by the human resources legislative framework

that applies to the public service as a whole. Often this framework includes central agencies like a

public service commission charged with regulating recruitment, promotion, training and various

staff relations issues. Furthermore, public service legislation often provides a regime for collective

bargaining, union or staff association representation, terms and conditions of employment

including remuneration, and such issues as pensions.

79. Revenue authorities, as a rule, are not part of the formal public service, and therefore they are

subject to a different human resources regime, often one more akin to a private sector company.

For example, in many countries, the RA is subject to an industrial relations law (or labour

relations law) that determines the union/management and collective bargaining environment. The

remainder of the human resources regime is the set of policies on human resources issues that is

approved by the Board of the RA.

80. The human resources framework has a profound effect on the options for the initial staffing of

the RA, particularly since it is the public service HR framework, along with transitional provisions

in the enabling legislation, which will determine what happens to existing tax and customs

department employees.

The implications for tax and customs employees

81. The approach to initial staffing is the issue that will likely be of greatest concern to the employees

of the existing departments. The approach that the government decides to take in this regard will

determine the extent to which existing employees of the tax and customs departments become

employed in the new RA, get placed in other departments in the public service, or are retired from the

public service. More importantly, the approach will determine the process and sequence of the events

that will transpire, and what rights and benefits each employee has in a particular circumstance. This

is a wide range of possibilities and this subject is likely to generate anxiety and concern among many.

82. The range of options possible is discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter. What must

be emphasized though is the importance of consultation and communication with staff. Without

full and timely consultation, employee concerns become exaggerated, unfounded rumours

develop and perception whether founded or not becomes reality.

83. Employees will want to know as soon as possible their options, the time available before

they will be required to make any decision, and the nature of any benefit to which they might

be entitled. It will also be important that employee records are up-to-date so that employees can

make informed decisions based on accurate records of years of service, etc.

32 Technical Notes and Manuals 10/08 | 2010

84. Employees will also want information on a variety of issues, such as what happens to their

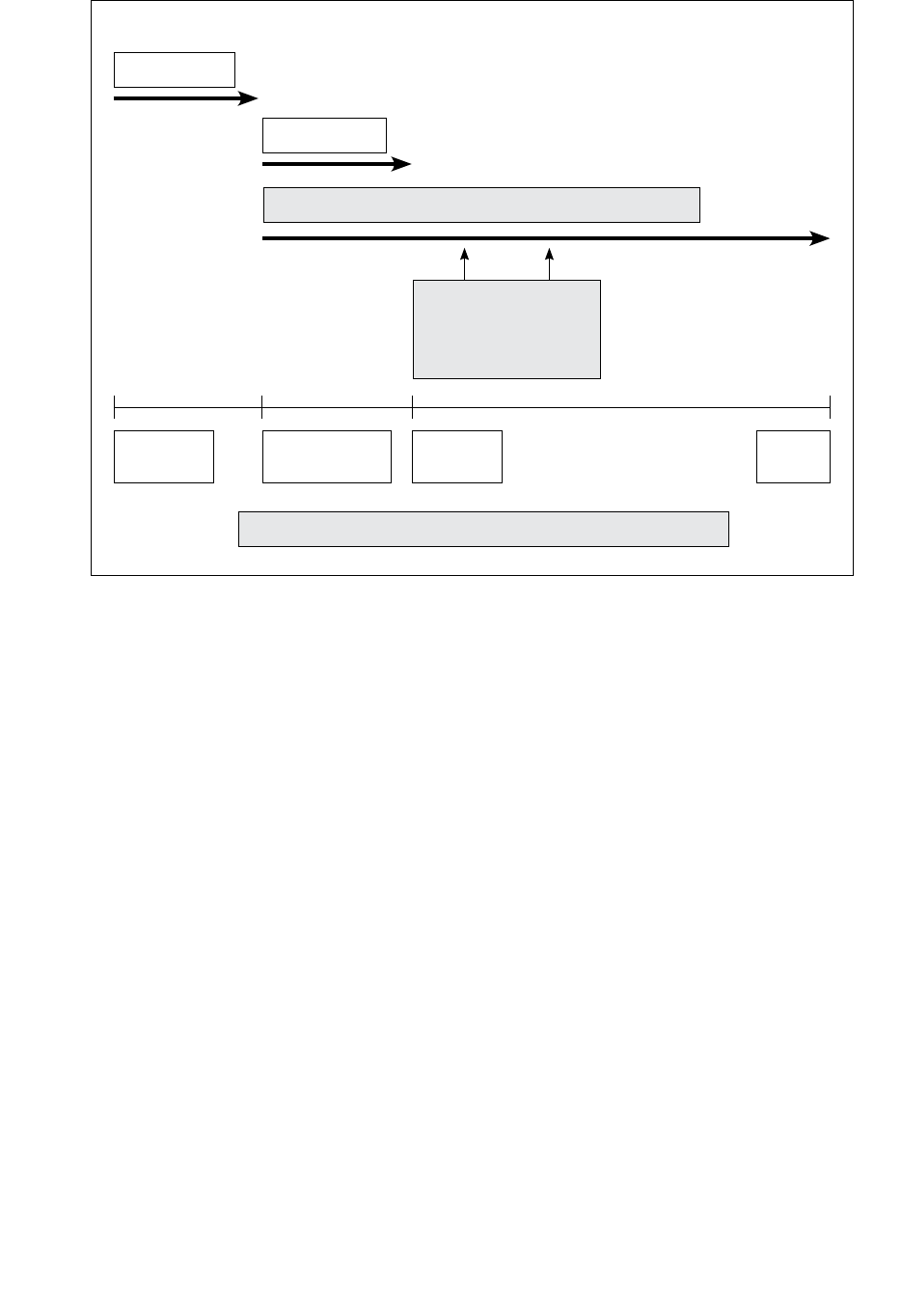

sick leave and vacation leave entitlements, their pensions, etc. In addition, employees will want to