70 Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17 (S1):70-74

Review Article

Putting the pyramid into action: the Healthy Eating

Index and Food Quality Score

Eileen Kennedy DSc RD

Dean, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA

Consumption patterns are changing globally. As a result both researchers and policy makers require simple,

easy to use measures of diet quality. The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) was developed as a single, summary

measure of diet quality. The original HEI was a ten component index based on the US Dietary Guidelines and

the Food Guide Pyramid. Research on the HEI indicates that the index correlates significantly with the RDA’s

for a range of nutrients and with an individual’s self-rating of their diet. The revised HEI provides a more dis-

aggregated version of the original index based on the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Within each of

the five major food groups, some foods are more nutrient dense than others. Nutrient Density algorithms have

been developed to rate foods within food groups. The selection of the most nutrient dense foods within food

groups lead to a dietary pattern with a higher HEI. The implications of using the HEI and nutrient density to

develop interventions are discussed in this presentation.

Key Words: Diet Quality, Nutrient Density, HEI

INTRODUCTION

More and more countries worldwide have developed or are

developing national food based dietary guidelines. A recent

report indicates that there is remarkable similarities in the

food based guidelines that have emerged, most noticeably

the emphasis on whole grains, fruits and vegetables.

1

In

addition to the emergence of dietary guidelines, there has

also been a call in the research and policy communities to

develop simple indicators to measure diet quality. This

paper discusses the development and use of the Healthy

Eating Index, a single, summary measure of diet quality. In

addition, a food quality score used to rate the nutrient

density of individual foods is presented.

Healthy Eating Index

The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) was developed in the mid-

1990’s to provide a single, summary measure of overall

dietary quality.

2

The HEI was intended to provide a way to

evaluate diet quality at a given point in time, as well as

method for monitoring changes in the food patterns over

time.

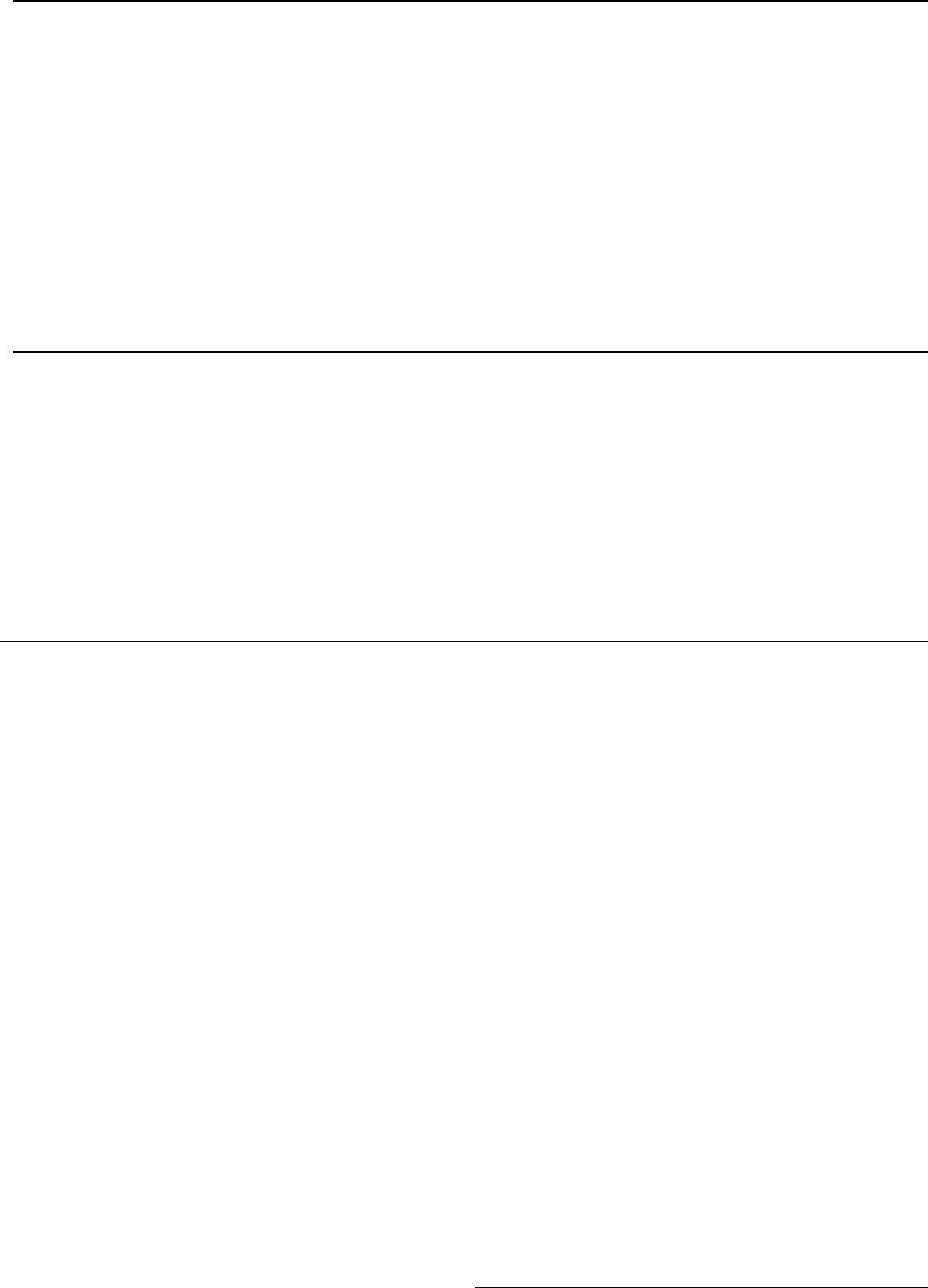

The HEI is a ten component index (see Fig. 1). The first

five components of the index are based on the five major

food groups of the 1992 USDA Food Guide Pyramid –

grains, fruits, vegetables, meat and alternates and milk.

3

Components six to ten are based are aspects of the 1995

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

4

including total fat,

saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium and variety. Each of the

ten components ranges in score from zero to ten.

The criteria for scoring each of these ten components is

provided in figure 2. Thus the composite HEI score can

potentially range from a minimum of zero to a maximum

score to 100.

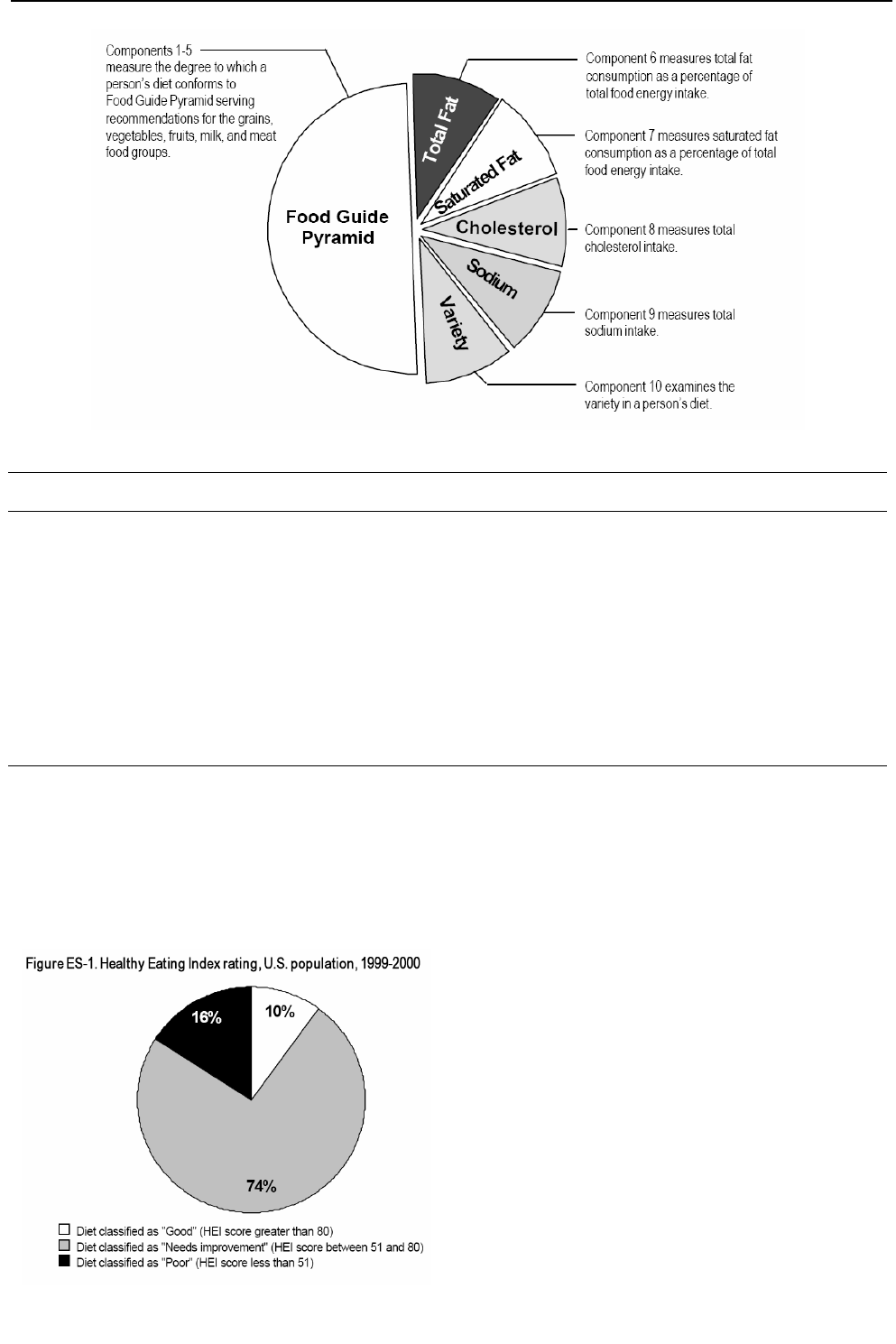

Figure 3 provides an illustration of the distribution of the

HEI scores for a representative sample of the U.S. popula-

tion in 1999-2000.

5

The major portion of the sample has an

average HEI in the range of 51 to 80 and category that is

defined as “needs improvement”. Only 10% of the popula-

tion has an HEI that is characterized as “good” with a HEI

above 80; similarly 16% of the population has an HEI

described as “poor”, falling in the range of 50 or less.

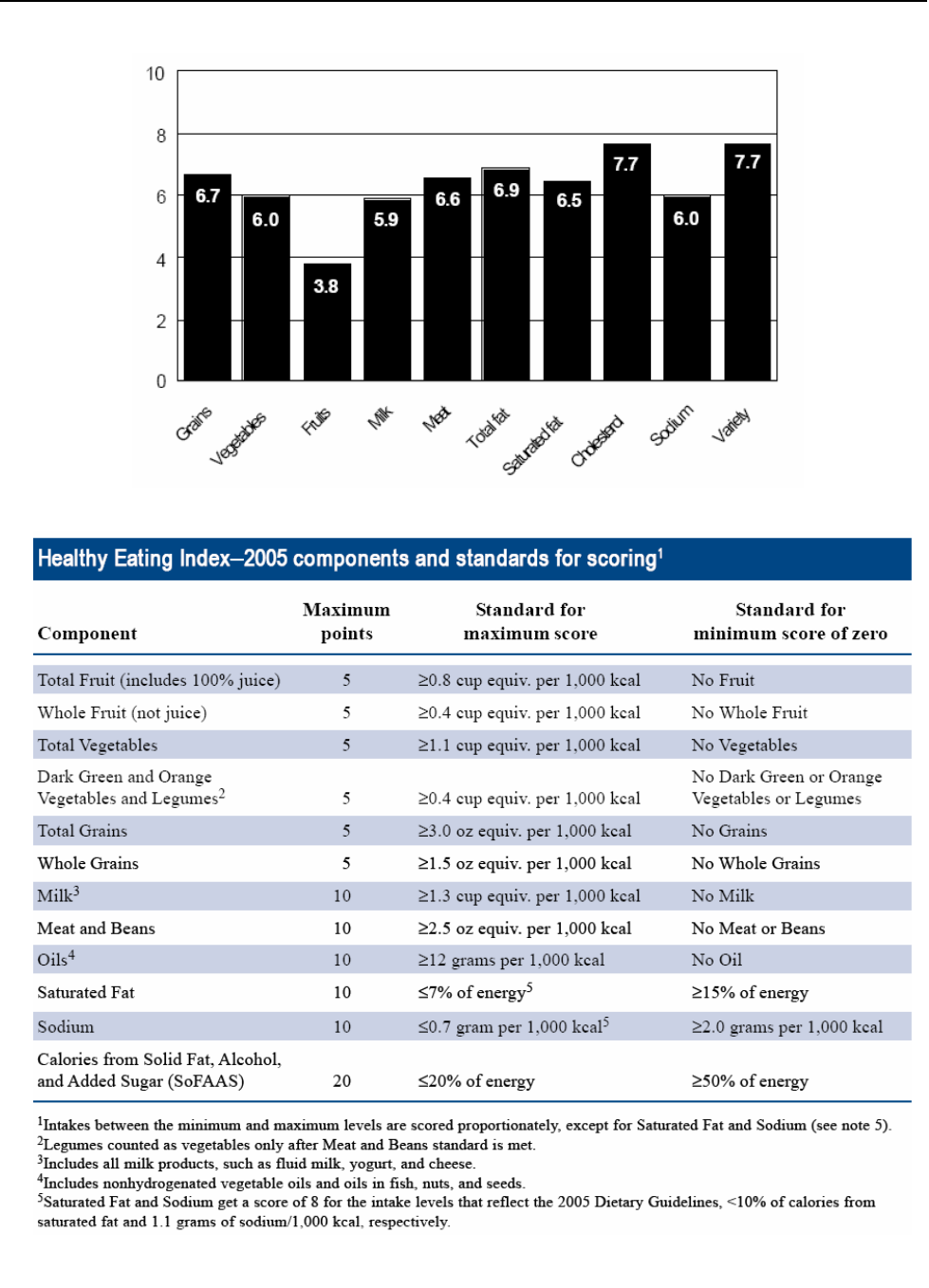

The mean scores for each of the ten components are

shown in figure 4.

5

By far, the lowest score – 3.8 – is

found for the fruits group. Scores for other HEI compo-

nents range from 5.9 to 7.7. The average total HEI tends to

fall in the range of 62 to 64 and there is little variation in

the population over time in the HEI.

6

This last statistic

appears to indicate that on a population level it is difficult

to improve the HEI in a short period of time.

Data from a representative sample for the period 1994-

1996, were used to validate the HEI. The HEI correlated

positively, significantly with a range of nutrient intakes.

2

In addition, the HEI was linked to an individual’s self

perception of their diet. Thus a person who self rated their

diet as poor or fair, were more likely to have a low HEI

than were individuals who rated their diets as good to

excellent.

2

Finally, a person’s HEI correlated with an individual’s

Body Mass Index (BMI) computed from self reported

Corresponding Author: Dr. Eileen Kennedy, Dean, Friedman

School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston,

MA

Tel: 617 636 3702; Fax: 617 636 3794

Email: Eileen.kenned[email protected]

Manuscript received 9 September 2007. Accepted 3 December 2007.

E Kennedy 71

Figure 1. Components of the HEI

Score range

1

Criteria for maximum score of 10 Criteria for minimum score of 0

Grain consumption

0 to 10

6-11 servings

2

0 servings

Vegetable consumption 0 to 10 3-5 servings

2

0 servings

Fruit consumption 0 to 10 2-4 servings

2

0 servings

Milk consumption 0 to 10 2-3 servings

2

0 servings

Meat consumption 0 to 10 2-3 servings

2

0 servings

Total fat intake 0 to 10 30% or less energy from fat 45% or more energy from fat

Saturated fat intake 0 to 10 Less than 10% energy from saturated

fat

15% or more energy from saturated fat

Cholesterol intake 0 to 10 300 mg or less 450 mg or more

Sodium intake 0 to 10 2400 mg or less 4800 mg or more

Variety 0 to 10 8 or more different items in a day 3 or fewer different items in a day

1

People with consumption or intakes between the maximum and minimum ranges or amounts were assigned scores proportionately.

2

Number of servings depends on Recommended Energy Allowance-see table 2. All amounts are on a per-day basis.

Figure 2. HEI Component Mean Scores

height and weight.

2

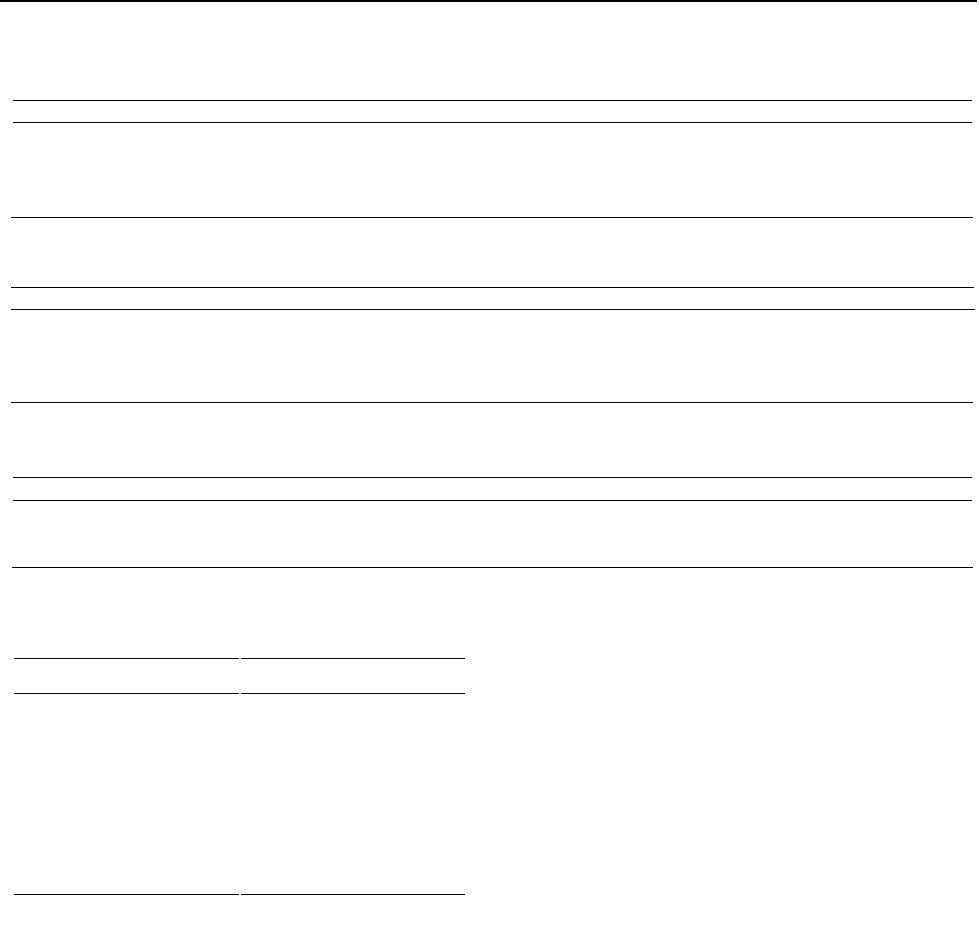

It was always the intention that the HEI would be up-

dated as newer science became available. Thus after the

release of the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

7

,

the HEI was revised. Figure five presents the updated

components of the HEI included the scoring system

used.

8

The major changes in the 2005 HEI include: an

emphasis on 50% of the fruit category coming from

whole fruit; an separate emphasis on orange and dark

green vegetables as well as legumes; a specification that

50% of the items from the grains category should be

whole grains; a separate category for discretionary calo-

ries from solid fats, alcohol and added sugars.

Nutrient Density Revisited

The 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

7

refer to the

concept of nutrient density throughout the report. While

the concept of nutrient density is not new, these latest

Dietary Guidelines put a renewed emphasis to a scientific

approach that was developed more than 30 years ago.

8

Statements such as

7

:

“Get the most nutrients out of your calories”

Figure 3. Overall HEI Score

72 Diet Quality

And

“Make smart food choices for every food group”

Reinforce the concept of nutrient density.

However, nutrient density is not an idea that is easily

understood by the consumer. In order to provide a

method that would allow consumers to rate the nutritional

quality of individual foods, a food quality score (FQS)

was devised.

9

Similar to the development of the HEI, the

food quality score was based on guidance provided by the

2005 Dietary Guidelines. The Food Quality Score .

9

is

based on two groups of nutrients. First a category called

shortfall nutrients was identified in the 2005 Dietary

Guidelines. Shortfall nutrients are those consumed in in-

sufficient quantities in the U.S. population and include

Figure 4. Mean for 1999-2000 – 63.8

Figure 5. HEI 2005

E Kennedy 73

fiber, Vitamins A, B12, E, C, D, folate, calcium, magne-

sium, iron and potassium. The second category is called

avoidance nutrients and as the name implies are ones

which, on average, need to be reduced in the American

diet. Avoidance nutrients include calories, saturated fats,

cholesterol, sodium and Trans fats.

A series of Food Quality Scores (FQS) were developed.

The Universal FQS (FQS1) applies one algorithm to all

foods using the ratio of shortfall nutrients to avoidance

nutrients. A second FQS was developed using algorithms

that were specialized to specific food group. The 2005

Dietary Guidelines were clear that foods from each of the

food groups were needed since each group provided

foods that were good and excellent sources of different

nutrients. Finally an algorithm with an expanded group

of 23 nutrients was developed.

Data from the USDA SR18 nutrient data base were

used to compute and compare the three different FQS.

Some points are worth noting. Nutrients added through

fortification were treated identically to nutrients naturally

occurring in foods. Mixed dishes composed of items

from more than one food group were decomposed into

their component food groups. For example, lasagna was

assigned proportionate parts to the grains, milk, meat and

vegetable groups for analysis of the food group specific

FQS.

Tables 1 through 3 illustrate the FQS using the three

alternative approaches. While the absolute FQS varies

with the method, the ranking of items within food groups

does not vary. Thus for example, on all three scores dry,

ice cream has the lowest ranking on the items in the dairy

group.

Table 4 illustrates the average universal FQS for the

five food groups. The FQS for fruits and vegetables, not

surprisingly, is substantially higher than for the other

three food groups.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The Healthy Eating Index has been used effectively for

monitoring, evaluation and has been adapted to a more

consumer friendly version.

10

Putting the concept of nutri-

ent density into practice is more of challenge. Further

research needs to be conducted to ascertain the effect of

Food Quality Scores, or indeed any food rating system,

on consumer food choices. Researchers have long known

that the major determinants of food choice are taste, price,

and convenience.

11

Whether promotion of a specific food

rating system will significantly influence food choices

and food consumption needs to be empirically determined.

A Food Quality System based on nutrient density can be

one tool that can facilitate more healthful food purchases

and dietary patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support for this work was provided by the Friedman School of

Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

Eileen Kennedy, no conflicts of interest.

Table 1. Dairy

Food Quality Score

Description

FQS

1

Universal FQS

2

Separate FQS

3

Expanded

Milk, dry, whole 3.25% milk fat

0.96 1.60 0.94

Milk, nonfat, fluid, with added vitamin A (fat free or skim)

4.30 7.62 4.30

Ice creams, vanilla

0.39 0.61 0.38

Table 2. Grains

Food Quality Score

Description FQS

1

Universal FQS

2

Separate FQS

3

Expanded

Bread, white, commercially prepared 0.98 1.11 1.34

Cake, angel food, commercially 0.62 0.59 0.71

Cereals ready-to-eat, GENERAL MILIS, TOTAL Corn Flakes 6.02 5.48 5.95

Table 3. Fruits

Food Quality Score

Description FQS

1

Universal FQS

2

Separate FQS

3

Expanded

Apples, raw, with skin 4.18 5.46 3.19

Oranges, raw, all commercial varieties 22.4 30.2 13.3

Table 4. Food Quality Score Averages

Food Group FQS Score average

Fruits 8.09

Vegetables 8.02

Grains 1.89

Dairy 1.24

Meats 1.03

Other 1.21

74 Diet Quality

REFERENCES

1. March of Dimes. Nutrition Today Matters Tomorrow: A

Report from the March of Dimes Task Force on Nutrition

and Optimal Development. March of Dimes: New York,

2001.

2. Kennedy E, Ohls J, Carlson S, K. Fleming. The Health Eat-

ing Index: design and application. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;

95:1103-8.

3. USDA. Food Guide Pyramid. Government Printing Office:

Washington DC, 1992.

4. Kennedy E, Myers L, Layden W. The 1995 USDA/DHHS

Dietary Guidelines -an overview. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;

96:234-7.

5. USDA, Center of Nutrition Policy and Promotion. The

Healthy Eating Index: 1999-2000. USDA: Washington, DC,

2002.

6. Basiotis P, Hirshman J, Kennedy E. Economic and socio-

demographic determinants of healthy eating as measured by

USDA’s Healthy Eating Index. Consumer Interests Annual.

1996;42:1-8.

7. USDA/HHS. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Governing

Printing Office: Washington, DC, 2005.

8. Zelman Kathleen and Kennedy Eileen. March/April 2005.

Naturally Nutrient Rich: Putting More Power on Americans’

Plates. Nutr Today. 40 (2).

9. Kennedy E, Rasca P, Dallal G, Lichtenstein A., Goldberg J,

Wilde P, Gleason G. Food Quality Scores: Nutrient Density

Revisited. Presentation at Experimental Biology Meeting,

San Diego 2006.

10. Kennedy Eileen and Richard Deckelbaum (editors). The

Nations Nutrition. ILSI Press: Washington, DC, 2007.

11. Frazao Elizabeth. America’s Eating Habits: Changes and

Consequences. USDA/ERS: Washington, DC, 1999.